Archive for the ‘Wot happened on this day’ Category

LANDSCAPE PHOTOGRAPHS ARE HISTORY: A book forward

.

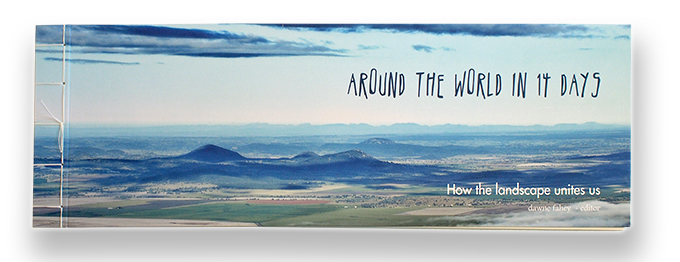

Recently I was asked to write an introduction for a limited edition book to compliment an exhibition of landscape photography entitled, Around the World in 14 Days: how the landscape unites us. The project featured seven contemporary Australian and international photographers, and was coordinated by Dawne Fahey of the FIER Institute with Sandy Edwards contributing to the image selection. The assembled body of work presented insights into how photographers ‘read the landscape, both visually and psychologically through their images.’

..

The photographs, created in Australia, Asia, New Zealand, USA and Colombia are intended to inspire viewers to consider how ‘elements effecting the landscape unite us, regardless of our differences or the distances that occur between us.’ Through the photographs there is also an intention that the ‘poetic fragments presented by the work will connect with the viewer’s own memories, experience, or sense of place.’

The exhibiting photographers are: Ann Vardanega (Australia), April Ward (Australia), Beatriz Vargas (Colombia), Gavin Brown (Australia), Michael Knapstein (USA), Robyn Hills (Australia) and Pauline Neilson (New Zealand) and the exhibition and book are on show at Pine Street Gallery, 64 Pine Street, Chippendale, Sydney until May 31, 2014.

See more at: http://www.pinestreet.com.au and http://fier.photium.com/around-the-world-in-14 – sthash.QPto0nz4.dpuf

The exhibition and book launch took place on May 20, 2014 at the gallery.

My essay discusses issues that relate to the premise of the exhibition as well as some personal observations of the idea of the photographer in the landscape. The essay is presented here and at the end of the post I have included a selection of images and installation photographs of the exhibition.

.

.

All landscape photographs are history

It is vain to dream of a wildness

distant from ourselves. There is none such.

In the bog of our brains and bowels, the

primitive vigor of Nature is in us, that inspires

that dream.

Henry David Thoreau, journal, August 30, 1856 [i]

Around sunset, Northern Territory time, a gathering of photographers will assemble in the central Australian desert and witness the now iconic sunset at Uluru. What they encounter will be a lived experience and there can be no doubt that cameras, both with and without telephony capability, will record the moment. Their images will bear metadata of the shutter speed, aperture, camera brand and model, the time, date and perhaps even its geolocation. These images will be cast into the Internet as evidence for friends and family to see – a private experience shared and made transferrable by technology.

What then of the subject of their gaze and activity – the landscape? For this rock in the desert, the next day will be a repeat of this photo ritual, and each day after, it will be repeated again and again. Does Uluru wait for its activation at each sunset and each shutter’s click? This landscape has experienced a few hundred million years of sunsets and its current fame as a photo celebrity, is a mere blip in its history. Every day will be different and thousands of days, well, not much change. However, today’s photograph, even a split second after its capture, is history.

For a number of years I have cultured the belief which was informed by a statement attributed to photographer Minor White: ‘No matter how slow the film, Spirit always stands still long enough for the photographer it has chosen.’[ii] My variation is that that landscape reveals itself to the photographer of its choosing. Writer and critic John Berger adds to this discussion by proposing that there is a ‘modern illusion concerning painting … is that the artist is a creator. Rather he is a receiver. What seems like creation is the act of giving form to what he has received.’[iii] Could it be then that the landscape is the director and commissioner of the image that the painter or the photographer makes, and that the photographer – the right photographer – is merely the vehicle for the landscape’s transformation of itself into an image?

Like portraits that have been made since the beginning of photography, and the documents of human endeavour, commerce, existence and experience – time, or rather the passage of time, has granted then their relegation to past. Each photograph in this book is then a history image. The moment and space depicted wrenched from the continuum of time by whatever forces brought together the photographer and the landscape. A landscape image at that moment of capture is at once the subject photographed and also a time machine. Viewed on its own by its maker the photograph can be a comfortable aide memoir, and operate just as a photo of a loved one or a family wedding would do in its frame on the mantelpiece – the photo exists, and so too the remembrance of subject it represents.

But photographs are more than things; they are experiences. Photographer Ansel Adams attributed special values and meaning to his landscape photographs and sought to represent the landscape as being more than what it was physically. Simon Schama in his book Landscape and Memory cites Adams as commenting that: ‘Half Dome [in Yosemite National Park] is just a piece of rock … There is some deep personal distillation of spirit and concept which moulds these earthy facts into some transcendental emotional and spiritual experience.’[iv] Adams inspired the American nation and created a tradition of environmentalism and black and white photography that continues today.

For Australian wilderness photographers Adams’ ‘emotion and spiritual’ connection with the landscape is salient. In the book Photography in Australia Helen Ennis discusses how photographers of this genre engage with their landscape subjects. She quotes Tasmanian photographer Peter Dombrovskis entering a ‘state of grace’ on bushwalks when, ‘days away from “civilization”, he felt what he described as, “a sense of spiritual connection with all around – from widest landscape to the smallest detail”’.[v] Ennis also comments that wilderness photographers use a range of techniques to ‘lift the experiences of viewing the photographs into a realm that goes beyond the human exigencies of normal daily life.’[vi]

In a book such as this, as we turn the pages, what is presented to us is the photographer’s concept or story encoded in visual form. As with Berger this may constitute the next generation of ‘giving and receiving’. They may have made the photograph/s with a specific objective in mind – a narrative angle, the idea of showing something that stirred them that they wanted to share – or – from the earlier discussion, what the subject wanted revealed. But in the space between the giver (the photographer and this book), and the receiver (you, the viewer), another hybrid narrative emerges. The photograph acts as a stimulus on the viewer and an idiosyncratic response is generated. Roland Barthes uses the term ‘detonate’ to describe being in front of a photograph. In Camera Lucida he comments that: ‘The photograph itself is no way animated, … but it animates me: this is what creates every adventure.’[vii]

In photographs we are not so much connected or united with the landscape, but rather the experience of the landscape and the trees, rivers, blades of grass and rocks that are represented in images. In effect we are united by the landscape of photography and the gift that we can share through it. We can then, through photographs enter into a Barthesian adventure. Perhaps these landscape photographs are more than history – they are: an experience shared, an unexpected encounter, an adventure. In your turning the pages – then pausing to view each group of images, to contemplate and consider the communiqué stimulated by them, these photographs become part of your history, your experience, and your adventure as well …

Dr Doug Spowart April 17, 2014

[i] Schama, S. (1995). Landscape and Memory. London, HarperCollins, epigraph, n.p.

[ii] http://www.johnpaulcaponigro.com/blog/12041/22-quotes-by-photographer-minor-white/

[iii] Berger, J. (2002). The Shape of a Pocket. London, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, p.18.

[iv] Schama, S. (1995). Landscape and Memory. London, HarperCollins, p.9.

[v] Ennis, H. (2007). Exposures: Photography and Australia. London UK, Reaktion Books Ltd, p.68.

[vi] ibid.

[vii] Barthes, R. (1984). Camera Lucida. London, UK, Fontana Paperbacks, p.20.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

The photographers retain all copyright in their photographs. Some texts are derived from exhibition documents. Text and installation photographs © 2014 Doug Spowart and Victoria Cooper

.

.

.

Cafe Scientifique: The Secret Life of Water – Vicky Speaks

.

.

.

Victoria Cooper

I Have Witnessed A Strange River says Cooper invited us to engage with a journey through the depths of water. She guided us through an unfamiliar place inter-twined with our daily lives where we witnessed the relentless cycle of life and death. Deep below the water’s reflecting surface, she showed us that a place primordial and alien yet intrinsic to us all, exists.

A SEGMENT OF VICKY’S PRESENTATION IS VIEWABLE HERE as a video

.

.’

BIO: Victoria Cooper is an artist with a PhD in Visual Arts researching the intersections of art and science. This interdisciplinary research is informed and inspired by her previous career in Human and Plant Pathology along with current interest in local and regional issues of land and water. During her 23-year arts career she has also worked across many forms of photographic technology–analogue to digital imaging; site specific documentation of performance; and artists’ books. In a collaborative practice with Dr Doug Spowart, she explores the post technological paradigm of photography as a cultural communication and a site-specific visual medium. This multi-methodological approach is applied in their current Place Project work in many regional communities. Cooper has exhibited in Australia and internationally and her work has been published in the Pinhole Resource Journal, the Le Stenope issue of French Photo Poche series and with Doug was included in the publication LOOK, Contemporary Australian Photography since 1980. Cooper’s artists’ books are held in national and private collections including the rare books and manuscript collections of the National Library of Australia and the State Library of Queensland.

.

.

Carl Mitchell

This is a Story About Water Too* The quality and supply of water is one of most important issues of our time. Water quality scientist Carl Mitchell from the Condamine Alliance discussed the quality of water in our waterways and the health of our aquatic systems – vital indicators of how well we are doing as a society. The waterways in the Condamine catchment are a precious resource for the communities in the region. They provide many benefits to support the economy, society and environment of the region. Due to extensive development across a number of sectors, the quality of waters in most of the catchment areas is poor. Studies and models predict that without appropriate additional management responses the region will be unable to meet the social and economic needs of the community while maintaining the ecological integrity of the natural systems supporting these needs. Carl discussed the state of the waters and what actions are needed in the future.

BIO: Carl is a water quality scientist, aquatic ecologist and integrated water resource management specialist with a passion for the water and the waterways of the Condamine Catchment in the headwaters of the Murray Darling Basin. Carl strongly believes that the quality of water in our waterways and the health of our aquatic systems is an indicator of how well we are doing as a society. This drives him to strive for clean water for the Condamine and healthy aquatic ecosystems for the Murray Darling headwaters. Carl’s work in the Condamine has focussed on restoring the iconic Condamine river and Carl has lead the team that won 3 prestigious national awards for the Condamine in 2012-2013. Carl has a history in Natural Resource Management in Queensland having worked for Reef Catchments in Mackay for 11 years as Waterwatch coordinator, Healthy Waterways Coordinator and Water Manager. In the Water Manager role at Reef Catchments Carl spent 2 years coordinating the Paddock to Reef program across the 6 reef regional bodies, before moving to the Condamine in 2011. Carl has been an Australian Youth Ambassador for Development in the Philippines, implementing Waterwatch and Landcare programs.

.

.

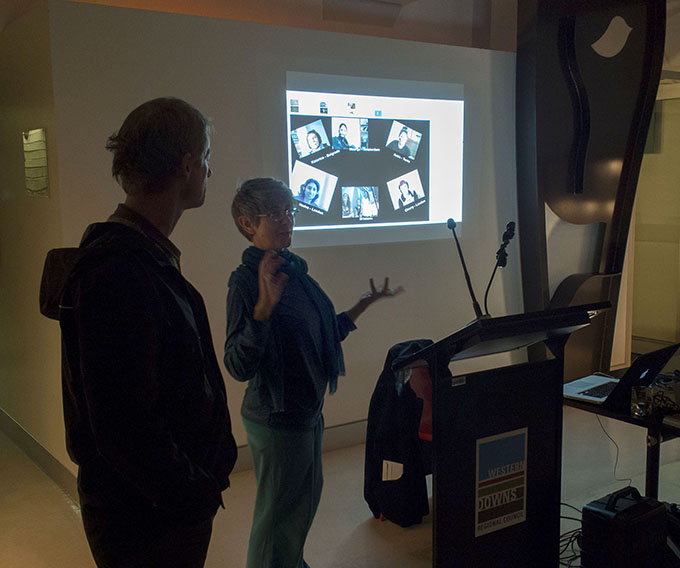

Igneous: James Cunningham and Suzon Fuks

The Igneous team shared its explorations of water as a topic and metaphor. They explained how Waterwheel is an interactive, collaborative platform for sharing media and ideas, performance and presentation. Attendees witnessed how Waterwheel investigates and celebrates this constant yet volatile global resource, fundamental element, environmental issue, political dilemma, universal theme and symbol of life. We were encouraged to explore and discover, share and collaborate, contribute and participate in their project and local activities.

Igneous presented Waterwheel as well as the FLUIDATA project supported by Arts Queensland, and introduced the audience to FLUIDATA workshop that we offered there.

BIOS: Igneous received funding from Brisbane City Council and Arts Queensland towards the development of the platform and it’s incorporation in the Waterwheel Installation Performance and associated residency at the Judith Wright Centre of Performing Arts, Brisbane. Igneous is a partnership between Cunningham and Fuks who have both given lectures, workshops, master-classes and labs in Australia, USA, Europe, India and Indonesia, in tertiary institutions, cultural venues and community contexts.

James Cunningham is a performance, movement and video artist, and the co-Artistic Director, along with Suzon Fuks, of Igneous Inc., (www.igneous.org.au) a Brisbane-based multimedia and performance company established in 1997 that has presented solo and ensemble stage shows, performance-installations, video-dance works and networked/online performances in Australia, Europe (Belgium, France, Switzerland, Germany, Poland), UK, Canada and India.

Suzon Fuks is an intermedia artist, choreographer and director, exploring the integration and interaction of the body and moving image through performance, screen, installation and online work (http://suzonfuks.net). During an Australia Council for the Arts Fellowship (2009-12), she initiated and co-founded Waterwheel, following which she has been a Copeland Fellow and an Associate Researcher at the Five Colleges in Massachusetts, continuing to focus her research on water and gender issues, and networked performance, as well as coordinating activities on Waterwheel.

* The Secret Life of Water Book Title by Masaru Emoto

* This is a Story About Water Too. Poem Title by Jayne Fenton Keane

Texts sourced from Dogwood Crossing material. Photos: Doug Spowart ©2014

.

.

WORLD PINHOLE DAY, 2014: Our Contribution

.

Round the [w]hole world on the 27th of April pinholers were out having fun – Making their images for the 2014 WPD. We’ve used our Olympus camera again and this time made duo self-portraits. This is the 10th year we have made pinhole images to support the WPD project!

.

.

VICKY’s Submission:

.

.

DOUG’s Submission:

.

.

Vist the WPD Site for other contributors: http://www.pinholeday.org/gallery/2014/

Our Past WPD images:

.

2013 https://wotwedid.com/2013/04/29/world-pinhole-photography-day-our-contribution/

2012 http://www.pinholeday.org/gallery/2012/index.php?id=1937&searchStr=spowart

2011 http://www.pinholeday.org/gallery/2011/index.php?id=924

HERE IS THE LINK to the 2011 pinhole video http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yk4vnbzTqOU

2010 http://www.pinholeday.org/gallery/2010/index.php?id=2464&Country=Australia&searchStr=spowart

2006 http://www.pinholeday.org/gallery/2006/index.php?id=1636&Country=Australia&searchStr=cooper

2004 Vicky http://www.pinholeday.org/gallery/2004/index.php?id=1553&Country=Australia&searchStr=cooper

2004 Doug http://www.pinholeday.org/gallery/2004/index.php?id=1552&Country=Australia&searchStr=spowart

2003 http://www.pinholeday.org/gallery/2003/index.php?id=615&Country=Australia&searchStr=spowart

2002 http://www.pinholeday.org/gallery/2002/index.php?id=826&Country=Australia&searchStr=spowart

.

.

CAN ART BRING CLOSURE TO COMMUNITY TRAGEDY?

.

CAN ART BRING CLOSURE TO COMMUNITY TRAGEDY?

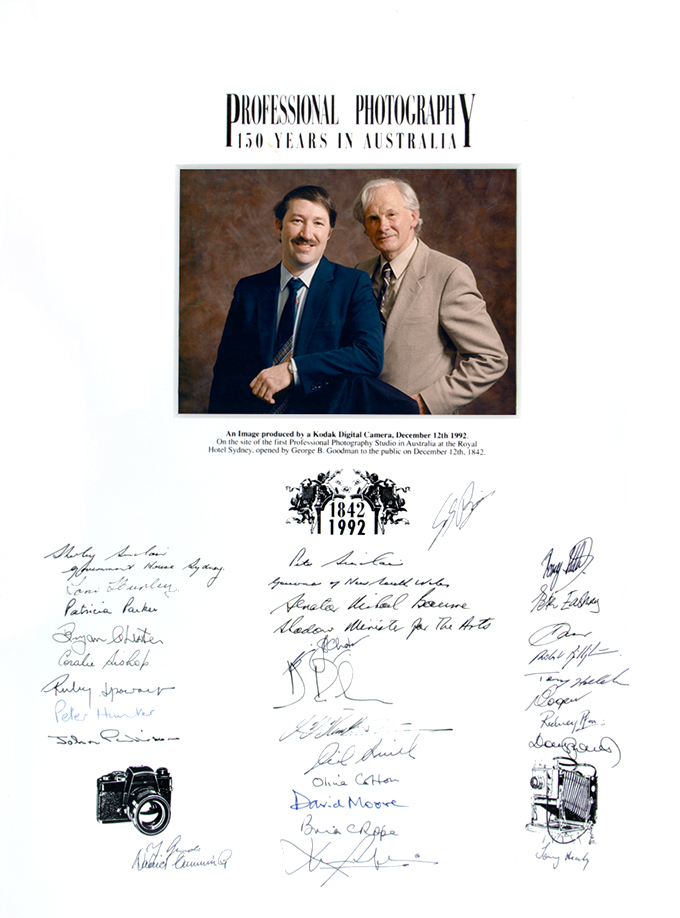

The exhibition SUNKEN HOUSES by Brad Marsellos and Heinz Riegler, Bundaberg Regional Art Gallery, March 12 – April 27, 2014

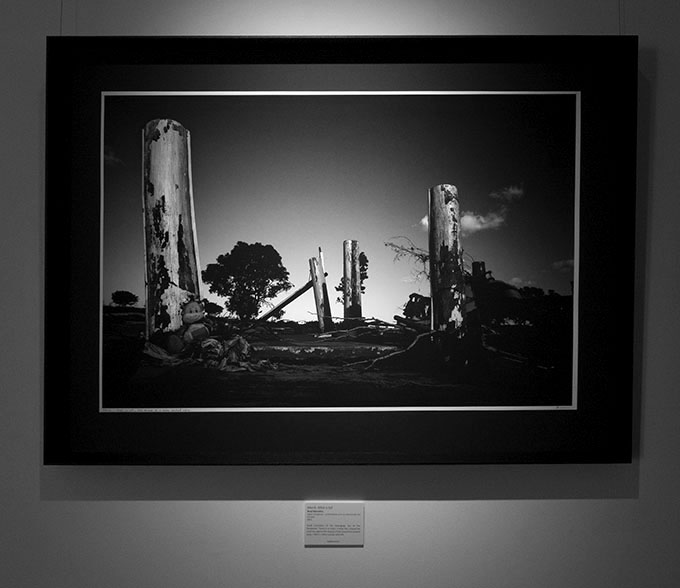

I’m standing in a dimly lit gallery surrounded by large-framed dark black and white photographic images. A somber soundtrack plays echoing the mood of the visual imagery. From outside the sound of rain pelting down enters the space and mingles with the exhibition’s audio. Rain is a sound that may normally not present a concern, particularly in a country frequently in drought, however the exhibition before me represents the effect that significant rain and runoff can have on our communities.

.

.

Just over twelve months ago, after days of torrential rain, the Burnett River at Bundaberg broke its banks submerging residential and commercial properties across the town. River cities historically deal with these events, however on this occasion the power of the river, and the duration of the flood, meant that after the water’s subsidence a significant area of urban space was obliterated. North Bundaberg suffered the most with houses washed off stumps, crashed into other homes and disappeared. What was left was utter devastation and a community dislocated, angry and in shock. The flood torrent had taken homes, belongings and also the sense of place and comfort that one feels in ‘being at home’.

Over those days the town had its heart wrenched from its foundations. Recovery, rebuild and move-on are the common expectations that usually follow such calamities. Government agencies and support groups rally in an attempt to facilitate the renewal and regeneration. However underlying the good works there still lingers memories, emotions and an all pervading the sense of loss.

When a community hurts the artist also shares that feeling and they may be called into service to make sense of, and perhaps through their art, help heal their community. So for local photographer Brad Marsellos, the story of the flood and the community became a 12-month project. Motivated to document and track the community’s response to the calamity Marsellos states he has: “… a strong passion for people and narrating lives, [and] believes photography allows the viewer to glance a moment in time and have the image take you on a journey.[i]”

The exhibition Sunken Houses, at the Bundaberg Regional Art Gallery, is the public presentation of Marsellos’ commitment to his community and this documentary project. In the gallery large black and white photographs are presented in wide bordered black frames. The photographs capture a sense of impending doom through dark dramatic light, and often-stormy clouds.

.

.

The curatorship and gallery craft involved in this show intentionally creates a space for contemplation of, and connection with, images of a community still in the shadow of the flood. All lighting in the gallery is subdued with the images spot lit creating islands of light. The accompanying soundtrack is described by the artists as ‘an immersive and emotive score’, and pervades the senses of the viewer. The composer was Heinz Riegler, a multidisciplinary artist who lives and works between Europe and Australia. The musical score was designed by Riegler to not only compliment the photographs, but to also represent his personal response to the stories and emotions of the Bundaberg community.

.

.

Marsellos’ images go beyond the plethora of documentary and news images that were broadcast during the event and in its aftermath. These photographs, their presentation, and the musical score, work to touch directly with deeply etched memories of the flood. Writer and intellectual Susan Sontag in her book Considering the Pain of Others[ii], makes the observation that ‘pictures allow us to remember’. She adds that:

Harrowing photographs do not inevitably lose their power to shock. But they are not much help if the task is to understand. Narratives can make us understand. Photographs do something else: they haunt us.

.

.

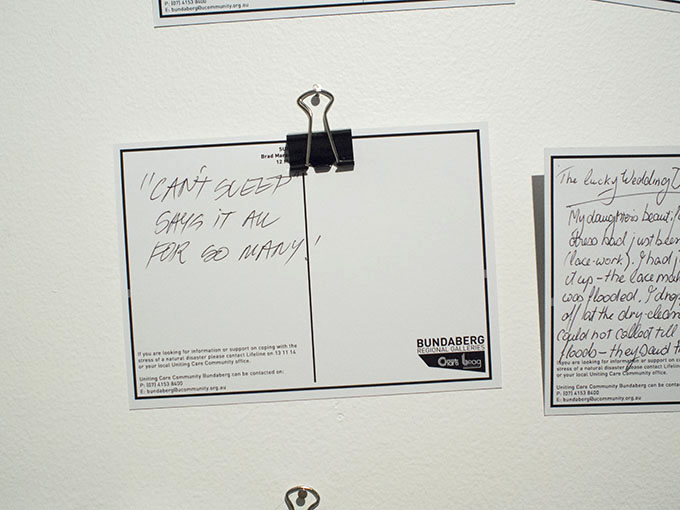

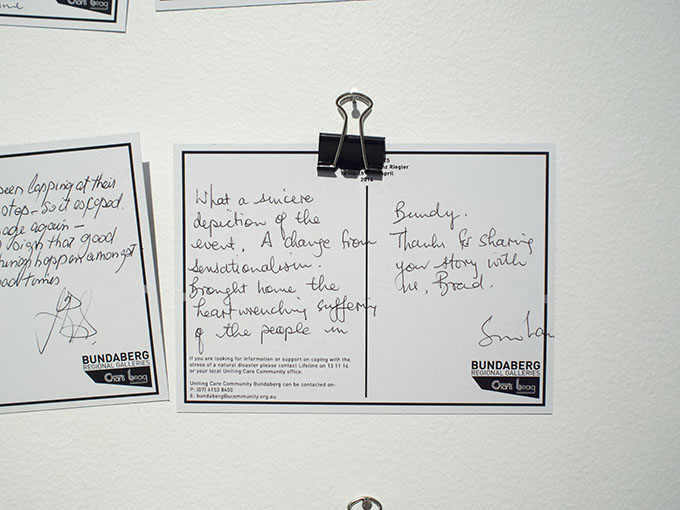

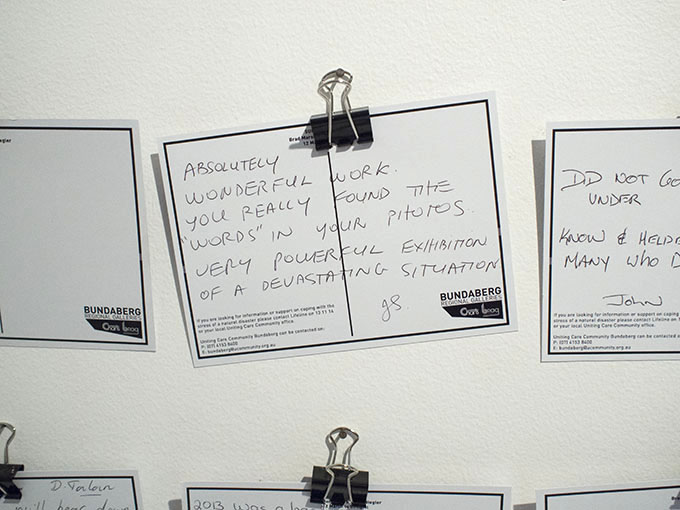

On their own these photographs may haunt and shock. Usually the viewer would leave the room taking with them the emotional state that was created in the gallery space. But this exhibition is different, there is a ‘message wall’ set aside in the gallery for visitors to tell their story – to express and share how they feel. Visitors either added to the wall or paused to read the cards and reflect upon the comments already posted. Perhaps this is evidence of the relevance that, ‘narratives can make us understand’, as Sontag suggests.

.

.

While the curation of the images, space and the musical score drench the gallery with a sense of tragedy and loss, the ‘message wall’ gives a release to the emotive tension. The combinative effect then of the exhibition is to create an overpoweringly emotional cathartic experience. First proposed by Aristotle, later by others including Freud, catharsis is considered as a psychotherapeutic treatment. Aristotle defined catharsis as: ‘purging of the spirit of morbid and base ideas or emotions by witnessing the playing out of such emotions or ideas on stage.’[iii] An exhibition like Sunken Houses may re-connect the community with memories and their experience of the event and through that connection provide much needed emotional healing.

Does the exhibition then function in a cathartic way? A Bundaberg News Mail report on April 16, 2014 published online, reported that the exhibition attendance had at that time broken all gallery records and stood at 2,500 visitors. In the article Brad Marsellos made a number of comments relating to the response of locals and out-of-towners to the exhibition and their reaction to the show.

“Every time I visit the space I read the many stories, messages of hope, recovery and continued struggles by members of our town that have been touched by this natural disaster.”[iv]

“Everyone has an experience of the floods and tornados – whether it be as an observer from afar, a flood affected resident or someone who is still rebuilding both physically and emotionally today and I’m honoured to think this exhibition is assisting some with their recovery process.”[v]

At a time when it seems that the importance of art and artists in the community is being downgraded by government defunding of art agencies, grants and opportunities for art education, it is humbling to see the effect that art can have on the community such as this. While the images may live on in the memories of those who witnessed the Bundaberg floods of 2013, the sensory experience of image and sound through the art of Marsellos and Riegler, will represent a compassionate and empathetic contribution – one that made a positive difference.

.

Doug Spowart

20 April 2014

[i] Gallery didactic panel

[ii] Sontag, S. (2003). Regarding the Pain of Others. New York, USA, Picador, p.89

[iii] McKeon, R., Ed. (2001). The basic works of Aristotle. New York, Modern Library, p.1458

[iv] NewsMail. (2014). “Sunken Houses exhibition draws a crowd.” Online. Retrieved April 16, 2014, 2014, from http://www.news-mail.com.au/news/sunken-houses-exhibition-draws-crowd/2231539/.

[v] Ibid

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

OTHER LINKS:

http://www.news-mail.com.au/news/sunken-houses-exhibition-draws-crowd/2231539/

Sunken Houses photographs © Brad Marsellos © soundtrack Heinz Reigler.

Installation photos and documentation of the artworks and review text ©Doug Spowart

.

My photographs and words are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/au/

.

.

.

.

.

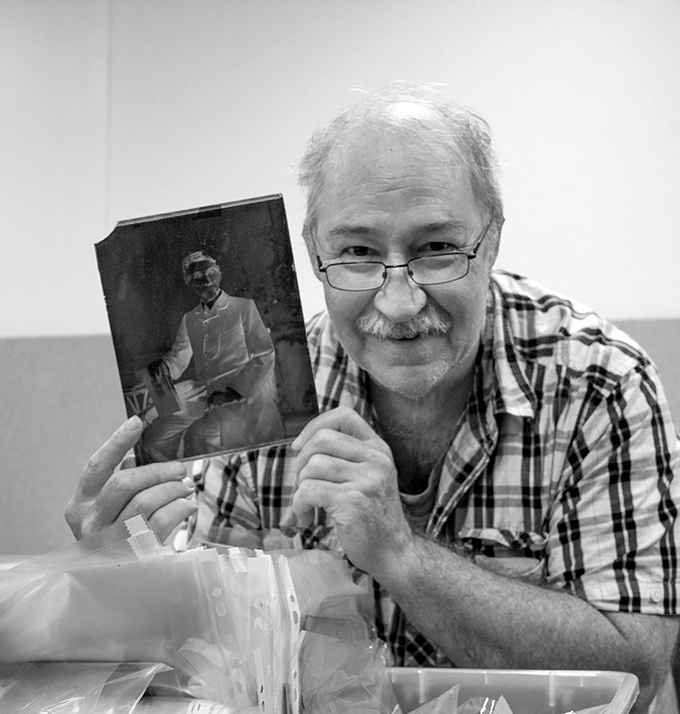

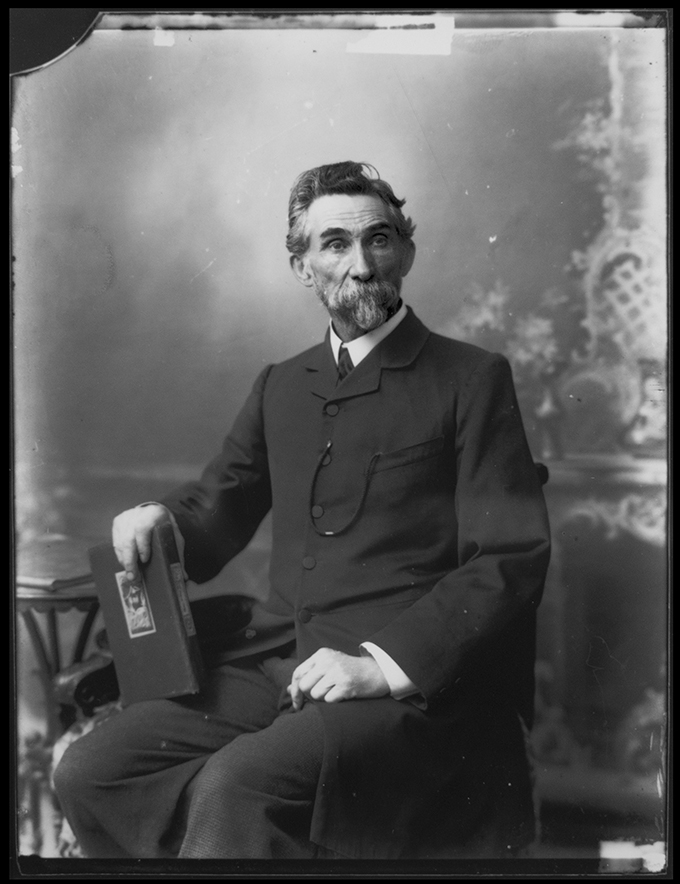

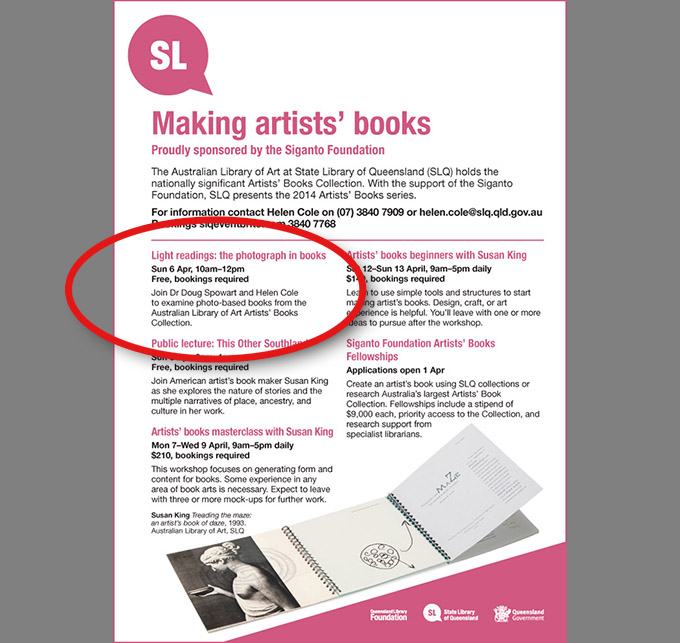

LIGHT READINGS: the photograph and the book – An SLQ White Gloves event

.

Light Readings: The photograph in books from the SLQ Artists’ Book Collection and the Spowart+Cooper Photobook Collection

.

On Sunday April 6 a group of around 25 artists book and photobook dillettantes attended a special ‘White Gloves’ event at the State Library of Queesnland. Assembled in the viewing room on level 4 was a selection of artists books and photobooks that addressed the topic of the photograph and the book. The 43 books were drawn from the SLQ’s Australian Library of Art Artists’ Book collection, the SLQ General Library, supplemented by books from the Spowart+Cooper Photobook Collection. The book’s selection was curated by SLQ Senior Librarian Helen Cole and Doug Spowart. Those attending the event were given a presentation by Doug Spowart to introduce the rationale for the selection. A discussion paper by Spowart is included in this blog post along with a bibliography of the selected books.

.

Doug Spowart’s discussion inspired by the ‘Light Readings’ event: A nomenclature for photos in books

For one hundred and fifty years the making of ‘quality’ photographs had been almost exclusively the domain of the professional practitioner. Outside of the professional photography scene vernacular photography, made popular due to the enabling technologies of ‘you press the button – we do the rest’ companies like Kodak, usually produced results that were of an inferior standard. There were of course exceptions – ‘prosumers’, as we would call them today, image-makers from the camera club movement, dilettantes and artists whose visual acutance and mastery of process suited photography.

Today digital technology has interceded and now anyone can make photographs. From a range of informed sources it is easy to predict that nearly a trillion photographs will be made in 2014. These images from phone camera snaps to video grabs, from high-end pro digital cameras to surveillance satellites, as well as a plethora of straight and enhanced images will be made and used for a range of outcomes. It seems that now anyone can make a photograph and almost anything can be done with it.

Like photography the publishing of books was once a closed world, as it required specialist processes, skilled artisans and financial entrepreneurship. But this powerful structure of gatekeepers too has also been dissolved by the empowering digital technologies of computers, software, computer-to-press and print on demand workflows. Making books has never been easier. Photographers particularly have embraced the opportunity and launched a revolution creating all kinds of photobooks to extend the bland form of the traditional photobook. Bruno Ceshel, founder of the photobook publishing and promotion enterprise Self-Publish Be Happy, comments that:

From the stapled fanzine assembled in a student bedroom to the traditionally printed photobook, these publications not only reshape our understanding of the medium but offer exciting and sometimes radical ideas. (Ceschel 2011)

.

Whilst photographers have embraced this new found direct publishing paradigm artists have made books with photos in them for decades. For them the processes of printmaking and multiples that they employ, along with access to printing press technology, is accessible and ‘doable’. Additionally artists have experimented with communication concepts that included the democratic multiple publications. Artists employ a range of media and the photograph was just another tool that they could access to create their art.

A significant connection between photography and the artists book is discussed by Anne Thurmann-Jajes and Martin Hellmold in their 2002 exhibition and catalogue ars photographica. They state that: ‘In very general terms, it is possible to say that half of all artists’ books produced to date have been based on photographs.’(Thurmann-Jajes and Hellmold 2002:19). It is interesting to note that the first book of the modern American artists book genre is Ed Ruscha’s book of photographs entitled Twenty-six Gasoline Stations.

The artist’s use of photography has created a degree of frisson. A point of contention for photographers was their ownership over the term ‘photographer’. Essentially photographers claimed that while artists may have made photographs, only photographers made ‘real’ photographs – artists just took photographs. Ruscha provocatively denounced the preciousness of the fine art photography movement that came out of the 1960s and announced that all he wanted out of photography was ‘facts, facts, facts.’ (Rowell 2006:24)

Thurmann-Jajes and Hellmold go further in that they propose differences between the artist and the photographer in the conceptual aspects of making a book based on photographs:

The authors of photo books followed photographic tradition, according to which the photograph as such was decisive, becoming the bearer of meaning. … By contrast to the photo book, the artists’ book is not the bearer, but the medium of the artistic message. (Thurmann-Jajes and Hellmold 2002:20)

.

Interestingly, the photobook and the artists book share a lost history that Johanna Drucker discusses in her 1995 book, The Century of Artists’ Books. She states that:

The photographic book became a standard of artists’ book activity, and its history belongs to the early 20th century in which the concept of the book as an artistic form was taking on a new, vital identity. (Drucker 2004:63)

.

Drucker adds:

These were works which were considered avant-garde, experimental, and innovative when they were made; they broke with the formal conventions of earlier book production, establishing new parameters for visual, verbal, graphic, photographic, and synthetic conceptualization of the book as a work of art … they were part of a history which was temporarily forgotten at the time artists’ book emerged in the 1960s. (Drucker 2004:63-4)

.

Despite these shared histories and theories of ‘differences’ the nature of the creative process, the disciplines of artist and photographer may present an interesting conundrum. Nancy Foote, for example, may question the ‘us and them’ argument by her observation in a 1976 article in Artforum, The Anti-Photographers that: ‘For every photographer who clamors to make it as an artist, there is an artist running a grave risk of turning into a photographer.’ (Foote 1976:46)

Today the photograph continues to pervade all kinds of books by artists, artists–photographers, photographers and photographer-artists in collections like the Australian Library of Art at the State Library of Queensland. At this time it is important to review the field of creative book production that utilises the photograph and consider what has been created to date and in the SLQ collection, as well as look for emergent trends.

In this research project Senior Librarian Helen Cole and I have collaborated to bring together a selection of books to survey the nature of the photo and the book. Whilst most books have been sourced from the SLQ Artists’ Book collection some books have come from the SLQ general area and some, mainly emergent photobooks have been drawn from my personal collection. In bringing these 43 books together in the one ‘white gloves’ space there has been an ability to create come kind of order from the divergent practice.

It would take a courageous and brave commentator to propose a definition or a canon for the photo and the book. Instead I will suggest a spectrum of activity and assign some characteristics that may aid those interested in the topic to compare, sample and discuss. I will use the term nomenclature as it best describes the devising or choosing of names for things in this type of discussion.

As the visible light spectrum has a rainbow of seven main colours this discussion has seven as well. Each has a specific characteristics and terms associated with it – although, at times certain books may challenge attempts to place them within this spectrum. The 7 colours are:

1. Red – The ‘Classic’ trade photobook

2. Orange – Print on demand trade-like photobook

3. Yellow – Emergent – PhotoStream* [of Consciousness] or Insta-photobook*

4. Green – Photozine*/ broadsheet / newspaper

5. Blue – Experimental’ or ‘Freestyle’ artists book

6. Indigo – Artists book

7. Violet – ‘Classic’, ‘Book Arts’, Livre d’artiste book

*Names I have considered to best describe these emergent forms

.

This spectral approach accepts the notion that the use of the photograph may be by either photographer or artist, and the nature of their creative products may enable their books to reside in generic areas. In many ways the transition of the rainbow metaphor from red to violet could represent the pure book forms of the photographer at one end and the purest artist form at the other at the other. This suggests that 1-4 would be photobooks conceived and produced by photographers. And those books in 4-7 would be principally books made by artists using photography. And at times the nature and form of the book may defy this nomenclature and be in a grey area, or a tint or shade, or even a blend of colour opposites!

Just as Johanna Drucker found when she attempted to define the artists book my categorising the practitioner’s discipline and the type or style of a book that they make also may be challenging. Drucker came under fire even though she predicted that her proposition would ‘… cause strife, competition, [and] set up a hierarchy, make people feel they are either included or excluded’ (Drucker 2005:3). More recently, in 2010, Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden from the Centre for Fine Print Research at the University of the West of England sought to define the canon for the artists book in the 21st century. They did this by creating a survey of world practitioners of book making by artists in every conceivable outcome, including the emergent eBook. They found that the heirarical form of a tree diagram was ‘too rigid and too concerned with process’ (Bodman and Sowdon 2010:5). They discovered that their respondents wanted to alter the diagram to satisfy the, ‘cross-pollination that is often required by artists’ and added in, ‘connectors across, up and down to bring seemingly disparate disciplines together.’ (Bodman and Sowdon 2010:5)

Rather than a rigid definitive structure, I present this spectral organization a guide where we can bring some concepts into a critical debate that will extend the ideas, and the motivations, behind those who create these communicative devices. Ultimately researchers, and those interested in engaging with and exploring the nature of the photo in the book, will add their voices to the conversation. Then new dialogue, scholarship and opportunities for thought on the topic will advance understanding of the book that carries its message with the photograph.

At the end of this blog post I have included the bibliography of selected books for the ‘Light Readings’ event.

Dr Doug Spowart April 14, 2014

References:

Bodman, S. and T. Sowdon (2010). A Manifesto for the Book: What will be the canon for the artist’s book in the 21st Century? A Manifesto for the Book: What will be the canon for the artist’s book in the 21st Century? T. S. Sarah Bodman. Bristol, England, Impact Press, The Centre for Fine Print Research, University of the West of England, Bristol.

Ceschel, B. (2011). “The Best Books of 2010.” Retrieved June 6, 2011, from http://www.photoeye.com/magazine_admin/index.cfm/bestbooks.2010.list/author_id/68/.

Drucker, J. (2004). The Century of Artists’ Books. New York, Granary Books.

Drucker, J. (2005). “Critical Issues / Exemplary Works.” The Bonefolder: An e-journal for the bookbinder and book artist 1(2): 3-15.

Foote, N. (1976). “The Anti-Photographers.” Artforum September: 46-54.

Rowell, M. (2006). Ed Ruscha Photographer. Gottingen, Steidl Publishers.

Thurmann-Jajes, A. and M. Hellmold, Eds. (2002). ars photographica: Fotografie und Künstlerbücher. Weserburg, Bremen, Neues Museum

.

A Bibliography of the selected books

From the Artists’ Book Collection of the Australian Library of Art, State Library of Queensland and the Spowart+Cooper Photobook Collection

Red – The ‘Classic’ trade photobook

American Cockroach

Photographs by Catherine Chalmers

Essays by Steve Baker, Garry Marvin, and Lyall Watson

Aperture, 2004

(Spowart+Cooper Photobook Collection)

Afghanistan, or, The perils of freedom

Stephen Dupont 1967- ; Jacques Menasche 1964-; Stephen C Pinson; New York Public Library : 2008

Steam : India’s last steam trains

Stephen Dupont 1967- ; Mark Tully

Stockport : Dewi Lewis :1999

Foundphotos / DickJewell

Dick Jewell

London : s. n. :1977

FromMontelucotoSpoleto : December1976

Sol LeWitt 1928-2007.

Eindhoven Netherlands : Van Abbemuseum ; Weesp Netherlands : Openbaar Kunstbezit :1984

Journey of a wise electron

Peter Lyssiotis 1949- ; PeterLyssiotis 1949-.; PeterLyssiotis 1949-.

Prahan, Vic. : Champion Books :1981

Eat : Jan-Mar 2001

Jo Pursey

Sydney, N.S.W. : J. Pursey :2001

Tour of duty : winning hearts and minds in East Timor

Matthew Sleeth 1972- ; Paul James (Paul Warren), 1958-

South Yarra, Vic. : Hardie Grant Books in association with M.33 :2002

Signs of Australia

Richard Tipping 1949-

Ringwood, Vic. : Penguin Books :1982

Intimations : with selected poetic responses by Michele Morgan

Gordon Undy

Surry Hills, NSW. : Point Light :2004

Orange – Print on demand trade-like photobook

Various fires and MLK

Scott L. McCarney 1954-

Rochester, N. Y. : VisualBooks :2010

Reportage : a retrospective 1999-2009.

Robert McFarlane 1942-; Jacqui Vicario; StephenDupont 1967-; National Art School (Australia); Momento Pro.

Bondi Junction, N.S.W. : Reportage :2010

Flashback : SE Queensland flood event January 2011

Julie White

Strawberry Hills, N.S.W. : Momento :2011

Yellow – Emergent PhotoStream* [of Consciousness] or InstaPhotoBook*

Iris Garden

Wiliam Gedney

Designed by Hans Seeger

Little Brown Mushroom, 2013

(Spowart+Cooper Photobook Collection)

Moved Objects

Georgia Hutchison and Arini Byng

Perimeter Editions

Melbourne, Australia, 2013

(Spowart+Cooper Photobook Collection)

Lost horizons

Scott L. McCarney 1954-,

Rochester, NY : ScottMcCarney/Visual Books :2008

Call of the wild

Matthew Sleeth 1972- ; Josef Lebovic Gallery.

Sydney N.S.W. : Published by Josef Lebovic Gallery :2004

Signed up : 22 postcards

Richard Tipping 1949-

Newcastle, N.S.W. : Artpoem :c2010

Green – Photozine*/ broadsheet / newspaper

Radiata, 2013

Jacob Raupach

(Spowart+Cooper Photobook Collection)

.

LBM Dispatch #6: Texas Triangle

Alec Soth and Brad Zellar

Little Brown Mushroom, 2013

Edition of 2000

(Spowart+Cooper Photobook Collection)

Blue – Experimental’ or ‘Freestyle’ artists book

Ten menhirs at Plouharnel, Carnac, Morbihan, Bretagne, France

Jihad Muhammad aka John Armstrong 1948-

Hobart Tas. : J. Armstrong :1982

Detour ; Kõrvaltee

Christiane Baumgartner 1967- ; Lucy Harrison 1974-; Grahame Galleries + Editions.

Leipzig, Germany : C. Baumgartner & L. Harrison :2004

No diving II : evidence

Peter E. Charuk

Hazelbrook, N.S.W. : P.E. Charuk :2005

The story of the gorge

Victoria Cooper 1957-

Toowoomba, Qld. : V. Cooper :2001

Supernova

Victoria Cooper 1957- ; Photographers of the Great Divide.

Toowoomba, Qld. : Photographers of the Great Divide :2005?

Space + Time

Ken Leslie ; Grahame Galleries + Editions.

Atlanta, Ga. : Nexus Press :2002

The river city : eyewitness document

Helen Malone 1948-

Yeronga, Qld : H. Malone :2011

Tonguey

Ron McBurnie 1957-

Townsville, Qld. : R. McBurnie :1996?

Portrait of an Australian

Jonathan Tse 1967-

Robertson, Qld. : J. Tse :1998

[Eleven]

Marshall Weber 1960- ; Christopher Wilde; Sara Parkel; Alison E Williams; Isabelle Weber; Booklyn Artists Alliance.

New York : Booklyn :c2002

Posted

Normana Wight 1936- ; Numero Uno Publications.

Milton, Qld. : Numero Uno Publications :2009

High tension

Philip Zimmermann ; Montage 93 : International Festival of the Image (Rochester, N.Y.)

Rochester, NY : the author :1993

Indigo – Artists book (Inkjet – gravure – photopolymer – screenprint)

Lost and found : a bookwork

Lyn Ashby 1953-

Vic. : ThisTooPress :2007?

The ten thousand things

LynAshby 1953-

Victoria : Lyn Ashby, Thistoopress :2010

Solomon

JanDavis 1952-

Lismore : J. Davis :c1995

Limes

Tommaso Durante 1956- ; Chris Wallace-Crabbe 1934-; Elke Ahokas

North Warrandyte, Vic. : Tommaso Durante :2011

Terra Australis

Tommaso Durante 1956- ; Kay Aldenhoven

Warrandyte, Vic. : TommasoDurante :2003

Homeland

Noga Freiberg 1962- ; Peter Lyssiotis 1949-.; Masterthief Enterprises

Burwood, Vic. : Masterthief :2003

Deeply honoured

Fred Hagstrom ; Densho Digital Archive.; Carleton College (Northfield, Minn.). Archives.

Saint Paul, Minn. : Strong Silent Type Press :2010

Cars of the fifties : book number 247

Keith A. Smith 1938-

Rochester, N.Y. : KeithSmith :2006

Violet – ‘Classic’ ‘Book Arts’ Livre d’artiste book

Through closed doors : 7 paraclausithyra

Susan J. Allix 1943-

London : S. Allix :2005

A gardener at midnight : travels in the Holy Land ; from drawings made on the spot by Yabez Al-Kitab

Peter Lyssiotis 1949- ; Brian Castro 1950-; David Roberts 1796-1864.; Nick Doslov; David Pidgeon; State Library of Victoria.; Masterthief Enterprises.; Renaissance Bookbinding.

Melbourne : Masterthief :2004

New branches on an old tree

Susan Purdy ; Blue Moon Press.

Melbourne : Blue Moon Press :2006

List concludes.

.

.

.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

.

.

Text: © 2014 Dr Doug Spowart Photos: ©2014 Victoria Cooper and Doug Spowart

.

.

.

.

SWITCHING LANES: A new art show @ Uni of Southern Qld Gallery

.

Our camera obscura work and Centre for Regional Arts Practice Survey Books are included in this show.

USQ MEDIA RELEASE: Shining a light on the art behind the teachers

WE KNOW they must be good at their craft, right? After all, they are the ones responsible for teaching tertiary students in this region all about sculpture and painting and drawing and photography and graphic design and ceramics. They are the best in their fields. But all too often the artistic endeavours of our local educators is not seen by audiences because they are simply too busy to exhibit, or reluctant to sing their own praises, or far too focused on the raising the profile of their students’ work instead of their own. That’s where Simon Mee – Associate Lecturer (Collections Curator and Arts Management) at University of Southern Queensland steps in.He is curating an annual series of exhibitions featuring the artist behind the teacher.

Last year it was the work of local high school teachers that was showcased in an exhibition called “Not Just A Day Job”; this year the light will be shone on our tertiary educators in the “Switching Lanes” exhibition opening in the USQ Arts Gallery on April 1. “I don’t think we always get to see the art behind the educator,” Mr Mee said. “But an exhibition series like this allows teachers in the area to engage with each other and support the value of what we all do. “It’s also good to flip things over and show students what teachers can do and let the teachers lead by example.”

The “Switching Lanes” exhibition does not have a theme – artistic educators from USQ, the Bremer and Southern Queensland Institutes of TAFE were given carte blanche to create what they want. This approach guarantees enjoyment for audiences – there may be a few surprises amongst the artworks – but also provide the greatest learning opportunities for students.

“The upside for students is that they get to see artists push and play with their craft,” Mr Mee said. “It’s living practice, – it will have a raw edge – and if it’s a disaster, then students will learn from seeing that as well. Art is not about creating a product, but about taking risks and growing. It’s all about doing what you love.”

Switching Lanes will open at the USQ Arts Gallery on April 1, and run from 9am to 5pm, Monday to Friday, until April 23. Entry is free.

.

.

.

Buildings with tattoos: First Coat Street Art Festival

.

THE FIRST COAT STREET ARTS FESTIVAL

.

The regional town of Toowoomba has been transformed over the weekend of the 21, 22 and 23 of February by a band of international, national and local artists, converting lane way walls into places of street art. Now dingy or dilapidated back lanes are the place where one can encounter art – or – has the art has come to us?

Street art or graffiti, whatever you call it was illegal with significant fines and community service being awarded those who were caught – perhaps even jail! Not being caught in the act as well as being outrageously brave in the places where work was to be placed and what it would say was what it was all about. Graffiti gave a kind of voice to a youth dispossessed by any means of being able to express how they felt or the creativity, perhaps even beauty, that can come from the nozzle of a spray can and a creative mind.

.

.

For years the domain of reckless and angry youth, the quickspray ‘tags’ adorned many buildings in public spaces. In time railway rolling stock became a moveable target for adornment. And while in the past, crews of official graffiti ‘strippers’ would attempt to remove these forms of creative expression it seems today that they have just given up–it’s far more interesting now to ‘graffiti-spot’ (like train spotting), at the train level crossings than ever before.

Working mainly in stencils the UK artist Banksy added to the genre’s acceptance in mainstream culture by his often ironic, humorous and insightful commentary. In his nocturnal art practice Banksy has maintained his anonymity and his works have passed into cult status.

Gone today it seems is the night work, gone too are dark clothes and a knap sack with a few cans–the limited palette of the graffiti criminal. Now, it’s all done in the light of day with the luxury of ladders, scissor lifts, fume masks and adoring fans. Most importantly is the visibility of the architectural canvasses being offered these artists.

.

.

National awareness, at least in Australia, arose through the acceptance and support of Melbourne’s laneway graffiti to the point where it has become a marketable tourist destination and has brought about the repossession of these once deserted grungy rear access thoroughfares.

Toowoomba’s ‘First Coat’ Street Art Festival has certainly left its mark on the town. Judging by the number of people walking around on the final day of the event, the media coverage and the deluge of Facebook posts by local residents it has captured the imagination of the community.

What remains is an assessment of the longer value of a project like this. Does the work look derivative of other places were this artform has been sanctioned? Will our children be doing graffiti workshops? – they are being offered in Toowoomba now, and will every wall become a tattoo-esque picture canvas? Will Toowoomba’s street art express community issues, concerns, icons and symbolism? Does the new street art become neutered in meaning becoming art entertainment, sanitised by its newfound sponsor – civil society and layers of government? Does any of this matter?

I’d like to think that out there somewhere – an angry young kid is expressing their life, concerns and messages to us by continuing in the foot-prints or sneaker-prints, and in the dark of night of those that have gone before…

Doug Spowart

24 February 2014.

.

.

LINK TO ABC Open + Toowoomba Chronicle pics+vids

http://www.abc.net.au/local/photos/2014/02/23/3950646.htm

http://www.thechronicle.com.au/videos/gimiks-born-first-coat/21759/

.

About First Coat:

Toowoomba’s CBD – 19 artists – 17 walls – 1 weekend

21st – 23rd February 2014

First Coat is a street art festival brought to by Toowoomba Regional Council and GraffitiSTOP, in partnership with Toowoomba Youth Service & Kontraband Studios.

Over 3 days, First Coat artists completed multiple large scale murals being painted, a Stupid Krap exhibition and artist talks were presented by Analogue Digital.

Locations:

2 Station St, 16 Duggan St, 12 Little St, 488 Ruthven St, 296 Ruthven St, 6 Laurel St,

2 Mark Lane, 9 Bowen St, 86 Russell St, 5 Mark Lane, 239 Margaret St, 70 Russell St, 80 Russell St

.

Proudly supported by:

Ironlak

Analogue Digital Creative Conference

Master Hire

40/40 Creative

Dulux

Coopers

ALL artworks © of the artists.

Photographic interpretations of the works ©Doug Spowart – Contact me if you were an artist and I will send images to you.

.

My photographs and words are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/au/

.

.

.

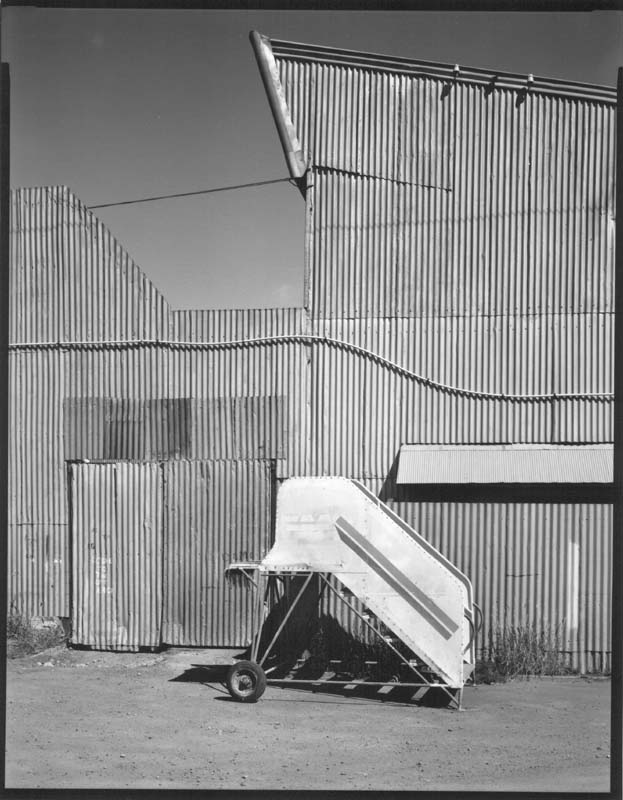

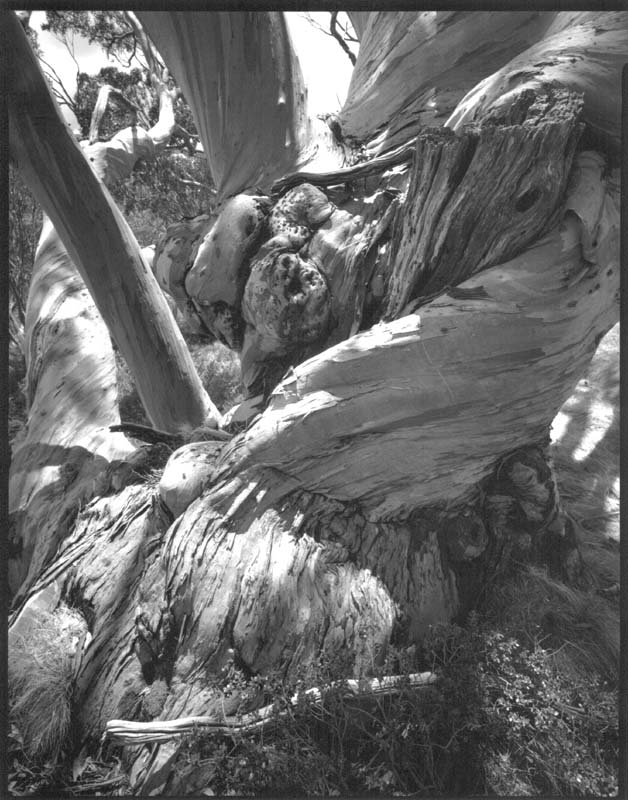

MARIS RUSIS: ORIGINAL PHOTOGRAPHS @ Gallery Frenzy, Brisbane

Masonic Hall, Barcaldine

.

The very nature of humanity is that each one who looks will see something different. So in these words, in this speech to open this exhibition, I’m in the privileged position to share what interests me about Maris Rusis’ original photographs. For a time I too was a disciple of the large format photography ‘zone’ – system discipline. I strove to develop what I’d call three skills: the conceptual – to see or previsualise; the technical to operate cameras and control chemistry; and the physical to lug the camera, all 50 kilos of it, to the place or subject of its use.

I found the romance of large format fieldwork is followed by the trial of the darkroom and the creation of a print reality – a manifestation of the subject as perceived by the photographer, at the time of capture. Chemistry, contact frames, darkness and the contemplative attention to time, temperature and agitation are an integral part of the process. So is, dare I say–image manipulation, dodging and burning-in to refine the distribution of tone, density and how these shape perception and direct the viewers eye as it rests on the image.

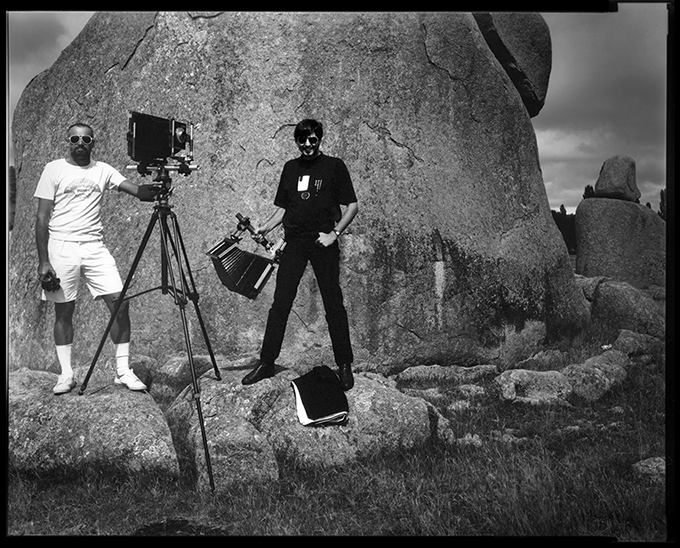

To bring an Australian light to the large format photograph Maris and I set out on a road trip from Brisbane to Canberra, Kosciuszko and Suggan Buggan in the late 1980’s. On this journey we shared rooms in cheap motels and backpackers, red wine and erudite conversation. Loading large format film holders in the cramped spaces of motel wardrobes and borrowed darkrooms we ventured into the high country and along roadsides. Photographing in the field was in part an endurance in the sweltering heat of mid-summer’s noon-day sun under the focussing cloth, and the privations of only being able to make 6-8 photographs a day – but each image was unique… a triumphant moment… a personal vision of light.

.

.

Part of our large format journey included special access to the vaults of the National Gallery of Australia’s photography collection. On opening, the light entered each solander box and we peered into the contents. We held prints by Weston – Brett included, Adams (Ansel–not Robert), Minor White, Emmet Gowan and others. These were the masters whose works we could generally only encounter on the pages of books usually at reduced size. I remember at the end of that day we stood on the exit parapet of the NGA, as it was in the old days, and you commented: “From today we can view the masters of large format photography with a new kind of arrogance”. Meaning that what we were achieving technically and conceptually matched anything we saw in the gallery’s collection. In reflection we did this in Australian light and of Australian subjects far removed from the well-trodden ground of the American tradition.

While I continued into the early 1990s hunting photographs with the SINAR 10×8 in the field, I was seduced to explore an expanding frontier of photography with Diana, pinholes and ultimately digital. Maris remained true to attitudes, values and approaches to photographic process and image quality that are the essence of the thing itself. Light-lens-silver – a direct and simple transference through photonics guided at every increment by the photographer and their vision for the subject before them. The plunge of the image-making world into digital technologies usurped and liberalised the terminology, in particular the words ‘photographer’ and ‘photograph’. Subsequently, it seems now with the emancipation of imaging anyone can be a photographer and anyone can photograph – it’s that easy.

There was a time when I, like many, thought a photograph was infinitely reproducible and that the darkroom was a machine for making multiples – but each was a little different. The speed and repeatability of digital imaging became the ‘machine’ where each print is identical. Now we can value each gelatine silver photographic print as a bespoke unique state object – a handcrafted image where as two can be identical. Maris once postulated a theory that the photographer, in printing their photographs – in particular with dodging and burning-in, created two images. The finished print is a secondary image of the subject before the camera – the first image being the negative, and as the photographer uses their hands to do shadowy light work they create a self-portrait primary image.

.

.

This evening, through the photographs that hang on these walls, an experience is shared. The title of the exhibition ‘Original Photographs’ may be exactly what they are. Our viewing position for this work as stated, is located in the digital age – where contemporary technology and process is arguably antithetical to the exulted practice that created these original photographic objects before us. Now I ask – should the provenance of these framed works make a difference to how we look at and think about these photographic prints? Should there be a precondition to viewing this work that requires a study of the technique, the myth, the challenges, incentives and the rewards of those who work this way, and how we as viewers should respond? Or should there be nothing of that. A photograph is before us – look, connect, interpret, respond … then, cast your view to the next.

What then of these photographs? Some may think that these prints may well be from a dinosaurian photographic tradition. For me their existence proves that the ritual continues and that the photographer’s vision and the seductive quality of the photographic prints that emerge from the photographer’s toil are still valuable contributions to the art. And therein lies the importance of Maris Rusis and his work. Few have walked his path in the sunshine of single-mindedness, about living one’s life totally absorbed, at whatever cost – family, friends, poverty and pleasure, all secondary to the pursuit of personal photographic nirvana, usually of the real large format kind. Edward Weston once stated: ‘My true program is summed up in one word: life. I expect to photograph anything suggested by that word which appeals to me.’ Maris Rusis and Weston have many things in common.

.

Doug Spowart

Written @ Girraween February 1, 2014.

.

.

.

Maris has written a reply to this post that adds to this commentary of his work:

.

It is an uncommon thing to invest some decades of effort in making pictures by one particular medium to the exclusion of all others. And an explanation is perhaps merited.

Firstly, everything Doug Spowart has covered in his blog is true and revalatory. It sets out key moments that propelled me in my committment to photography. And I thank Doug for the good start he gave me. But to keep going I had to support the conviction that my chosen medium has valuable properties that are not obtained or replicated by alternative means. I still continue to make pictures out of light-sensitive materials and offer by way of flagrant self justification the following essay:

In Defence of Light-Sensitive Materials.

The word photography was invented to describe what light-sensitive materials deliver: pictures that offer a different class of imaging from painting, drawing, or digital methods.

These “light-sensitive” pictures are photographs and the content of such pictures is the visible trace of a direct physical process. This is sharply different to painting, drawing, and digital imaging where picture content is the visible output of processed data. Some other imaging methods that do not process data include life casts, death masks, brass rubbings, wax impressions, coal peels, papier-maché moulds, and footprints.

There is a general idleness of thought that assumes any picture beginning with a camera is a photograph. Most casual references to digital pictures as photographs are motivated not by deceit but rather by the innocent and uncritical acceptance of the jargon “digital photography”; a saying which has become so banal and familiar that it largely passes unchallenged; except perhaps here, now, and by me.

I use light sensitive substances to make pictures because of the special relationship between such pictures and their subject matter. The wonder of this special relationship is also available to the aware viewer. Making realistic looking pictures long pre-dates photography. Old and new techniques include photo-realist painting, mezzotint, graphite drawing, gravure, and offset printing. Recently analogue and digital electronic techniques can deliver the appearance of abundant realism at trivial effort and cost . But although these pictures may mimic photographs but they do not invoke the unique one-step material bond between a subject and its photograph.

The physical and non-virtual genesis of pictures made from light-sensitive substances has far-reaching consequences:

Light sensitive materials are utterly powerless in depicting subject matter that does not exist. A true photograph of a thing is an absolute certificate for the existence of that thing; an existence proof at the level of physical evidence. Quite differently, data-based pictures at best approximate testimony under oath rather than evidence.

Light-made pictures require that the subject and the substances that will ultimately depict it have to be in each other’s presence at the same moment. True photographs cannot recreate times past. The future is similarly inaccessible. Since true photographs can only begin their existence in the fleeting present they constitute an absolute certificate that a particular moment in time actually existed.

Light-sensitive materials are blind to the imaginary, the topography of dreams, and the shape of hallucinatory visions. The option of making a picture from light sensitive materials offers an infallible way of distinguishing delusion from reality. A true photograph authenticates the proposition that the camera really did see something.

Light-sensitive substances neither selectively edit nor augment picture content. There is a one to one correspondence between points in a true photograph and places in real-world subject matter. This correspondence, also known as a transfer function, is immutable for all subject matter changes.

The sole energy input for a true photograph comes from an illuminated subject. The pre-existing internal chemical potential energy of the light-sensitive substances is sufficient to generate all the marks of which a photograph is composed. Other external energy inputs are not required. Remember, photography was invented in, described in, and works perfectly in a world without electricity.

Pictures made from light sensitive materials are different to paintings, drawings, and digital confections in that their authority to describe subject matter comes not from resemblance but from direct physical causation.

It is these unique qualities of true photography, its limitations and its profound certainties, that keep me committed to the medium as an integral and original form.

My light-generated pictures are produced one at a time, start to finish, and in full by my own hand. The work flow is mine. No part of it is down to assistants or back-room people toiling to flatter my skills so I will feel good about paying their fee. I will continue to make pictures out of light-sensitive substances even if it comes to the point where I have to synthesise those substances myself.

.

MORE IMAGES FROM THE SHOW:

.

.

All photographs © Maris Rusis. Photograph of the two photographers ©Maris Ruusis and Doug Spowart.

.

.

A BOOK for AUSTRALIA DAY, January 26, 2014

.

It’s Australia Day!! We have a photobook on display in the Two Doors Gallery in 85 George Street the ‘Rocks’, Sydney that is a commentary on Australia Day, that we created on Australia Day in 2010.

.

The collaborative book, called Australian Banquet, January 25/26, 1788 (variant #5), is a double-sided broadsheet cyanotype in rice paper, 37.6x77cm. There are 7 unique state variants of this work.

.

.

The artists’ statement for the work is as follows:

.

Across Australia on January 26, people consume food in celebration of a free and dynamic Australian culture. This work comments on the ‘turning of the page’ in Australian history that Australia Day represents. One day — January 25th 1788, Indigenous people feasted on a diverse banquet of bush tucker (as they had for thousands of years). The next day —a new paradigm arrived with the table setting of the First Fleet. Australia Day importantly is a time to re-examine the status of the Indigenous perspective and their knowing of land, culture and history and how it underpins all that is celebrated in the diversity and identity of post-colonial Australia.

.

.

How the work is to be viewed/read

1. At a tabletop setting view and contemplate the 25th of January side of the broadsheet.

.

2. Then, pickup the broadsheet and turn it over as if reading a book – Contemplate.

.

3. Finally hold the broadsheet up to a light thus enabling the interrelationship between the two

images to be considered. (Image shows variant #4)

.

Drop in to the gallery if you’re in Sydney.

If you happen to be in ‘The Rocks’ on Monday 27th, the public holiday come along to Two Doors and see Picturing the Orchestral Family – and a selection of photographs by Dawne Fahey – and hear the Carreon Family Quartet performance – Tango from 2 – 3. They will also perform February 2nd – same time. Performing daily @ 5.30 pm is flautist Chloe Chung – Two Doors is very lucky to have these young people from Sydney Youth Orchestras helping us celebrate this exhibition !

Have a Great Australia Day…!

.

© 2014 Dawne Fahey (gallery image) and ©2012 Doug Spowart+Victoria Cooper.

.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/au/

.

.

.