Posts Tagged ‘Maris Rusis’

1993 THE BRISBANE PHOTOGRAPHY SCENE: Ian Poole Guest Editor

From 1990 to 2001 I edited and published a journal called PHOTO.Graphy (ISSN 1038-4332 and earlier called ‘News Sheet’). This journal was created to fill a gap in the discussion, critique and commentary about a segment of the photography discipline within Australia. Occasionally I would engage guest editors to add their voice to the conversation. Ian Poole was the Guest Editor for Volume 4 #5 – Here is my Editorial introducing to Ian’s view of the art photography scene in Queensland in 1993.

Ian’s survey of the Queensland art photography scene makes for interesting reading nearly 25 years on… Mentioned in the survey are; Rod Buchholtz, Andrew Campbell, Ray Cook, Victoria Cooper, Marion Drew, John Elliott, Peter Fischman, Craig Holmes, Andrew Hurst, Chris Houghton, Susan Leway, Kerry James, Gail Newmann, Glen O’Malley, Charles Page, Graeme Parkes, Ray Peek, Howard Plowman, Rhonda Rosenthal, Maris Rusis, Doug Spowart, Ruby Spowart, Richard Stringer, Carl Warner, Jay and Younger. Charles A. von Jobin is also featured in the issue.

.

A PDF of the full issue is available HERE: PHOTO.G-Vol4n5r.

MARIS RUSIS: ORIGINAL PHOTOGRAPHS @ Gallery Frenzy, Brisbane

Masonic Hall, Barcaldine

.

The very nature of humanity is that each one who looks will see something different. So in these words, in this speech to open this exhibition, I’m in the privileged position to share what interests me about Maris Rusis’ original photographs. For a time I too was a disciple of the large format photography ‘zone’ – system discipline. I strove to develop what I’d call three skills: the conceptual – to see or previsualise; the technical to operate cameras and control chemistry; and the physical to lug the camera, all 50 kilos of it, to the place or subject of its use.

I found the romance of large format fieldwork is followed by the trial of the darkroom and the creation of a print reality – a manifestation of the subject as perceived by the photographer, at the time of capture. Chemistry, contact frames, darkness and the contemplative attention to time, temperature and agitation are an integral part of the process. So is, dare I say–image manipulation, dodging and burning-in to refine the distribution of tone, density and how these shape perception and direct the viewers eye as it rests on the image.

To bring an Australian light to the large format photograph Maris and I set out on a road trip from Brisbane to Canberra, Kosciuszko and Suggan Buggan in the late 1980’s. On this journey we shared rooms in cheap motels and backpackers, red wine and erudite conversation. Loading large format film holders in the cramped spaces of motel wardrobes and borrowed darkrooms we ventured into the high country and along roadsides. Photographing in the field was in part an endurance in the sweltering heat of mid-summer’s noon-day sun under the focussing cloth, and the privations of only being able to make 6-8 photographs a day – but each image was unique… a triumphant moment… a personal vision of light.

.

.

Part of our large format journey included special access to the vaults of the National Gallery of Australia’s photography collection. On opening, the light entered each solander box and we peered into the contents. We held prints by Weston – Brett included, Adams (Ansel–not Robert), Minor White, Emmet Gowan and others. These were the masters whose works we could generally only encounter on the pages of books usually at reduced size. I remember at the end of that day we stood on the exit parapet of the NGA, as it was in the old days, and you commented: “From today we can view the masters of large format photography with a new kind of arrogance”. Meaning that what we were achieving technically and conceptually matched anything we saw in the gallery’s collection. In reflection we did this in Australian light and of Australian subjects far removed from the well-trodden ground of the American tradition.

While I continued into the early 1990s hunting photographs with the SINAR 10×8 in the field, I was seduced to explore an expanding frontier of photography with Diana, pinholes and ultimately digital. Maris remained true to attitudes, values and approaches to photographic process and image quality that are the essence of the thing itself. Light-lens-silver – a direct and simple transference through photonics guided at every increment by the photographer and their vision for the subject before them. The plunge of the image-making world into digital technologies usurped and liberalised the terminology, in particular the words ‘photographer’ and ‘photograph’. Subsequently, it seems now with the emancipation of imaging anyone can be a photographer and anyone can photograph – it’s that easy.

There was a time when I, like many, thought a photograph was infinitely reproducible and that the darkroom was a machine for making multiples – but each was a little different. The speed and repeatability of digital imaging became the ‘machine’ where each print is identical. Now we can value each gelatine silver photographic print as a bespoke unique state object – a handcrafted image where as two can be identical. Maris once postulated a theory that the photographer, in printing their photographs – in particular with dodging and burning-in, created two images. The finished print is a secondary image of the subject before the camera – the first image being the negative, and as the photographer uses their hands to do shadowy light work they create a self-portrait primary image.

.

.

This evening, through the photographs that hang on these walls, an experience is shared. The title of the exhibition ‘Original Photographs’ may be exactly what they are. Our viewing position for this work as stated, is located in the digital age – where contemporary technology and process is arguably antithetical to the exulted practice that created these original photographic objects before us. Now I ask – should the provenance of these framed works make a difference to how we look at and think about these photographic prints? Should there be a precondition to viewing this work that requires a study of the technique, the myth, the challenges, incentives and the rewards of those who work this way, and how we as viewers should respond? Or should there be nothing of that. A photograph is before us – look, connect, interpret, respond … then, cast your view to the next.

What then of these photographs? Some may think that these prints may well be from a dinosaurian photographic tradition. For me their existence proves that the ritual continues and that the photographer’s vision and the seductive quality of the photographic prints that emerge from the photographer’s toil are still valuable contributions to the art. And therein lies the importance of Maris Rusis and his work. Few have walked his path in the sunshine of single-mindedness, about living one’s life totally absorbed, at whatever cost – family, friends, poverty and pleasure, all secondary to the pursuit of personal photographic nirvana, usually of the real large format kind. Edward Weston once stated: ‘My true program is summed up in one word: life. I expect to photograph anything suggested by that word which appeals to me.’ Maris Rusis and Weston have many things in common.

.

Doug Spowart

Written @ Girraween February 1, 2014.

.

.

.

Maris has written a reply to this post that adds to this commentary of his work:

.

It is an uncommon thing to invest some decades of effort in making pictures by one particular medium to the exclusion of all others. And an explanation is perhaps merited.

Firstly, everything Doug Spowart has covered in his blog is true and revalatory. It sets out key moments that propelled me in my committment to photography. And I thank Doug for the good start he gave me. But to keep going I had to support the conviction that my chosen medium has valuable properties that are not obtained or replicated by alternative means. I still continue to make pictures out of light-sensitive materials and offer by way of flagrant self justification the following essay:

In Defence of Light-Sensitive Materials.

The word photography was invented to describe what light-sensitive materials deliver: pictures that offer a different class of imaging from painting, drawing, or digital methods.

These “light-sensitive” pictures are photographs and the content of such pictures is the visible trace of a direct physical process. This is sharply different to painting, drawing, and digital imaging where picture content is the visible output of processed data. Some other imaging methods that do not process data include life casts, death masks, brass rubbings, wax impressions, coal peels, papier-maché moulds, and footprints.

There is a general idleness of thought that assumes any picture beginning with a camera is a photograph. Most casual references to digital pictures as photographs are motivated not by deceit but rather by the innocent and uncritical acceptance of the jargon “digital photography”; a saying which has become so banal and familiar that it largely passes unchallenged; except perhaps here, now, and by me.

I use light sensitive substances to make pictures because of the special relationship between such pictures and their subject matter. The wonder of this special relationship is also available to the aware viewer. Making realistic looking pictures long pre-dates photography. Old and new techniques include photo-realist painting, mezzotint, graphite drawing, gravure, and offset printing. Recently analogue and digital electronic techniques can deliver the appearance of abundant realism at trivial effort and cost . But although these pictures may mimic photographs but they do not invoke the unique one-step material bond between a subject and its photograph.

The physical and non-virtual genesis of pictures made from light-sensitive substances has far-reaching consequences:

Light sensitive materials are utterly powerless in depicting subject matter that does not exist. A true photograph of a thing is an absolute certificate for the existence of that thing; an existence proof at the level of physical evidence. Quite differently, data-based pictures at best approximate testimony under oath rather than evidence.

Light-made pictures require that the subject and the substances that will ultimately depict it have to be in each other’s presence at the same moment. True photographs cannot recreate times past. The future is similarly inaccessible. Since true photographs can only begin their existence in the fleeting present they constitute an absolute certificate that a particular moment in time actually existed.

Light-sensitive materials are blind to the imaginary, the topography of dreams, and the shape of hallucinatory visions. The option of making a picture from light sensitive materials offers an infallible way of distinguishing delusion from reality. A true photograph authenticates the proposition that the camera really did see something.

Light-sensitive substances neither selectively edit nor augment picture content. There is a one to one correspondence between points in a true photograph and places in real-world subject matter. This correspondence, also known as a transfer function, is immutable for all subject matter changes.

The sole energy input for a true photograph comes from an illuminated subject. The pre-existing internal chemical potential energy of the light-sensitive substances is sufficient to generate all the marks of which a photograph is composed. Other external energy inputs are not required. Remember, photography was invented in, described in, and works perfectly in a world without electricity.

Pictures made from light sensitive materials are different to paintings, drawings, and digital confections in that their authority to describe subject matter comes not from resemblance but from direct physical causation.

It is these unique qualities of true photography, its limitations and its profound certainties, that keep me committed to the medium as an integral and original form.

My light-generated pictures are produced one at a time, start to finish, and in full by my own hand. The work flow is mine. No part of it is down to assistants or back-room people toiling to flatter my skills so I will feel good about paying their fee. I will continue to make pictures out of light-sensitive substances even if it comes to the point where I have to synthesise those substances myself.

.

MORE IMAGES FROM THE SHOW:

.

.

All photographs © Maris Rusis. Photograph of the two photographers ©Maris Ruusis and Doug Spowart.

.

.

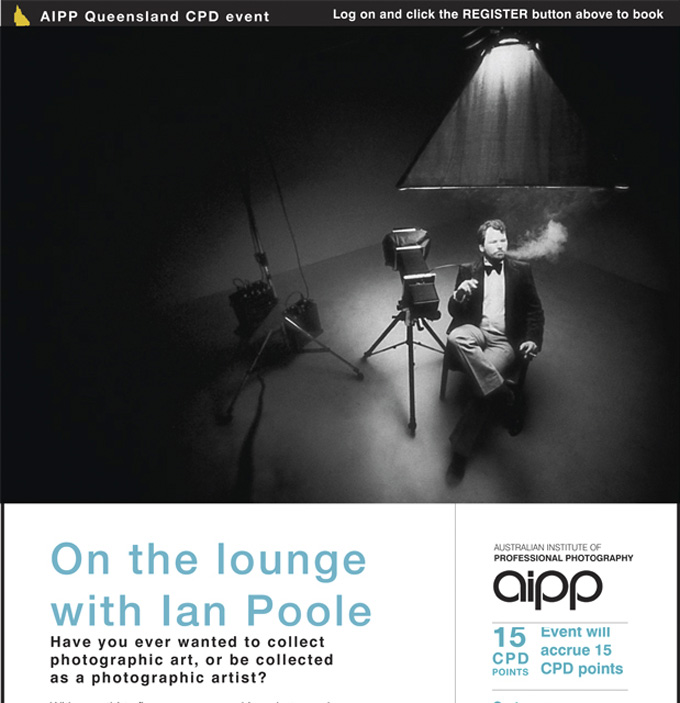

IAN POOLE: AIPP On the Lounge

Ian Poole is well placed to have an opinion about fine art photography and collecting photographs. He has been a major player in professional photography in Brisbane for nearly 40 years and is a respected AIPP judge with yearly invitations to also judge the New Zealand Institute of Professional Photography awards. Despite his professional photography connection he has been a part of a sector of the Queensland photographic art scene that extends from the early 1980s with Imagery Gallery, later with the Photographer’s Gallery and more recently with the Queensland Centre for Photography. He has completed a Graduate Diploma in Visual Arts from the Queensland College of Art and has been awarded an Australia Council residency in Tokyo. Adding to this he has curated photographic exhibitions in Japan (of Queensland photographers) and exhibitions in Australia (of local and Japanese photographers).

So when Poole offers commentary on aspects of the photographic art world of Brisbane and Queensland it should be something of an opportunity to connect with his extensive knowledge of the genre. Recently as part of the AIPP ‘On the Lounge’ lecture series Ian Poole presented to an assembled audience of around 40 a dissertation entitled, ‘Have you ever wanted to collect photographic art, or be collected as a photographic artist?’

Ian Poole began his presentation by reviewing recent art auction records for photographic artworks including those by Adams, Sexton and Dupain. Thousands, hundreds of thousands and even millions will change hands for well-known and rare works. The recent phenomena of Nick Brandt’s African work,which had been shown only weeks earlier in Brisbane, attracted some discussion. Perhaps some in the audience felt a little inspired by the possibility that, if they could enter the fine art field, that there was recognition and the possibility for a significant income to be made.

Poole introduced his collection of images that were hung on the walls and laid out on tables before the audience and discussed their histories and stories. For him the concept of ‘provenance’ elevated the importance of each work. A small Dupain image of the interior of the National Gallery in Canberra made during its construction was linked to his encounter with the work in a Brisbane gallery where it was purchased for a few hundred dollars. His most exuberant discussion related to a Joachim Froese diptych acquired when he swapped it with Joachim for a 4×5 enlarger. An expanded provenance trail led to it being loaned back to Joachim so that it could be displayed a QUT exhibition of his work.

A long-term friendship with north Queensland photographer Glen O’Malley presented some interesting provenance stories. O’Malley is not fully recognised for the significance of his practice in Queensland – he could probably claim to have had the first ‘photographic art’ exhibition in this state in the mid 1970s. Poole presented to the audience an image from O’Malley made as part of the Queensland Art Gallery’s 1988 Journeys North commission. The 20×24” black and white photograph showed a scene in Poole’s home where the O’Malleys were having dinner. The image was part of the accepted images for the Journeys North show and was subsequently published. Somehow Poole’s own life had become art photography itself.

Another photography collaborator presented by Poole was John Elliott. Well known for his documentation of country and western music and its heroes and doyens including Slim Dusty, Chad Morgan and Jimmy Little, Elliott is an enigmatic character of the photography scene. Ian spoke of John’s most recent show Gifted Country at the Caboolture Regional Art Gallery and his photobook publishing ventures. A recent journey to Townsville that Poole had shared with another of Queensland’s enigmatic photographers, Maris Rusis, resulted in a body of work by Rusis that dealt with the décor of budget north Queensland motel rooms. These small and fine gelatin silver fibre B&W prints presented to the audience the fact that traditional values remain key to some workers who continue to practice analogue photography in a digital world.

Question time brought up some difficult truths – Why does the Queensland Art Gallery/GOMA not seem to be collecting photography generated within this state? Did they ever collect? Some discussion related to the archival needs for conservation framing and presentation.

As a conclusion to the presentation Poole spoke of the way in which he and his photography acquaintances swapped and shared their works, and how much of his collection was built around the generosity of fellow photographers and their desire to share. He held a bundle of his own gelatin silver images up before the audience and made an offer that ‘you can have one of my prints this evening – and send a print to me as a swap. Start your collection this evening …’

While Ian Poole began his presentation with a review of the overtly mercantile auction scene, it seemed that his passion about photography, photographs, friends, shared experiences and the meaningfulness of the provenance of the works, that these things could not be commodified. He spoke of his collection of photos, books and ephemera as being an entity that would be bequeathed to his daughter Nicola, also a photographer and present at the talk. Through the audience he directed to Nicola to ‘treasure and look after these things … they were important, valuable – not only as the stories they depicted through their image on the front-side of the print, but also of the back-story of their origin and collection.’

There is no doubt that Ian Poole’s passion for photography and his understanding of how it operates at a personal and cultural level is something that was shared and communicated on this evening. And those present will be inspired to develop a new appreciation of what photographs are and what they can say about the human condition.

Doug Spowart May 20, 2012

An unusual meeting – Face-to-Face with an early portrait of one’s self – circa 1982 found in Poole’s collection