Archive for the ‘Exhibitions’ Category

MAUD GALLERY: TRANSLUCENCE: Jacqui Dean’s Xrayograms

.

.

TRANSLUCENCE: Jacqui Dean’s Xrayograms

Maud Creative Gallery June 18th – July 19th, 2014

6 Maud Street Newstead, QLD 4006

Ph 07 32161727

www.maud-creative.com

.

.

A comment about the work by the exhibition speaker Robert McFalane

In TRANSLUCENCE, photographic artist Jacqui Dean reveals Australia’s flora, both native and introduced – in radically new ways. Dean’s searching vision reduces flowers to their essential, sculptural shapes, translating them into exquisite, archival black and white prints. Calla lilies are seen as never before – with their curved flowers resembling the shape and texture of a crystal goblet. Dean’s delicate images of roses, through composition and digital magic, reveal interlaced petals that mimic the textures of a Tulle bridal veil.

Dean’s delicate, dancing images in TRANSLUCENCE mirror the elegance of Nature while resonating deeply with the work of artists as disparate as photographic pioneer William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) and the affectionate, intricate drawings of Nature by Albrecht Durer. (1471-1528)

Jacqui Dean is a talented Sydney architectural, corporate and fine-art photographer known for her rigourous sense of composition and peerless black and white printmaking skills. Twenty seven prints will be on display at Maud Creative Gallery during this first Brisbane exhibition of TRANSLUCENCE.

“Look deep into nature, and then you will understand everything better.”

ALBERT EINSTEIN (1879 – 1955)

‘Another Universe’ a review by Victoria Cooper

.

From the late 19th, and into the early 20th century there was a growing movement in the sciences and the arts that associated with Nature’s inherent resonance of form and structure from the microscopic to the cosmic. These new vistas and universes were recorded not only by the scientists’ hand but also by new developments in technology, notably the invention of the photographic process. Visual communication through imaging technologies continues to be an important tool in scientific research. But these images were not just useful as scientific evidence they were and continue to be inspiration for the creative work of artists and designers.

One noted exemplar utilising this visual medium was Karl Blossfeldt (1865-1932), a sculptor, metal craftsman and teacher. Blossfeldt began taking photographs of botanical specimens to use in his classes as ideas for students to create design forms from nature. But Blossfeldt’s work became very influential in the art, craft and design movement that popularised natural forms as templates for architecture, sculpture and 3D design work. His photographic documentation revealed abstract views of humble everyday roadside plants as visually interesting structural and aesthetic forms. As a result, Blossfeldt’s photographs also became renowned as works of fine art.

Jacqui Dean’s exhibition Translucence, at 2 Danks Street Gallery, Sydney, and now at Maud Gallery in Brisbane, is the result of artistic curiosity and visual investigation natural forms through the phenomenon of Xrays. Art in this respect is the revelation of the unseen, the beholding of the essence within ordinary objects or a transforming perception of the everyday experience. The photograph, or in this case ‘xrayograph’, seals the object within the frame safe from the changes and inevitable decay over time. At first glance these images could appeal to the naturalist or perhaps a student of design (after Blossfeldt). Yet a deeper – more poetic vision immanent in nature is also suggested through a more contemplative viewing of these images.

Some may argue that this is an uncomfortable clash between the modernist and the romantic, or the objectivity of scientific evidence and the subjective imagination. But could this work identify with a need to embrace a sense of wonder rarely seen within a super-hyped, virtual digital-image society? Dean’s work in Translucence is informed by the poetry of music and her life’s experiences and her prodigious professional practice in photography. However the rewards for the thoughtful viewer will be to share in her wonder of the natural world that surrounds and nourishes our everyday life.

Victoria Cooper . . . June 9, 2013.

.

.

MORE INFORMATION:

Jacqui Dean’s Website: http://deanphotographics.com.au/fine-art/

Interview by Gemma Piali of FBi Radio, Sydney: http://fbiradio.com/interview-jacqui-dean-on-translucence/

.

Xrayograms: © Jacqui Dean

Review text © 2013 Victoria Cooper

All exhibition opening photographs © 2014 Doug Spowart

.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

.

.

HeadOn–AddOn: Cooper+Spowart invited to participate

This year we were invited to participate in the 2014 HeadOn – AddOn event: Here are the details behind the event from the HeadOn Website…

.

.h

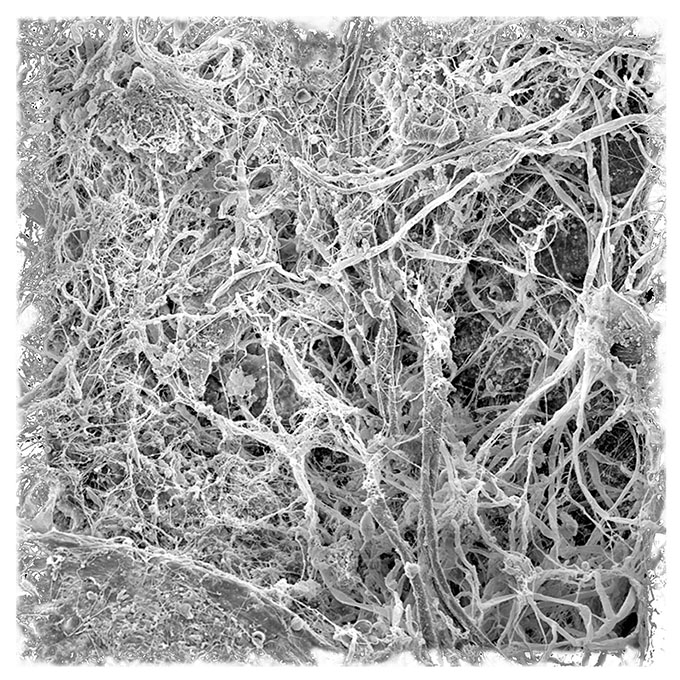

AND HERE ARE OUR IMAGES …

.

.

.

Part of the 2014 programme of:

.

.

© 2014 Cooper+Spowart

.

LANDSCAPE PHOTOGRAPHS ARE HISTORY: A book forward

.

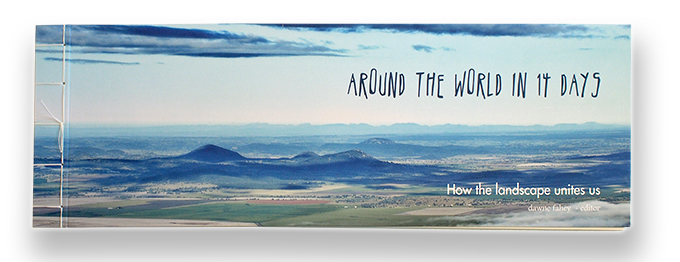

Recently I was asked to write an introduction for a limited edition book to compliment an exhibition of landscape photography entitled, Around the World in 14 Days: how the landscape unites us. The project featured seven contemporary Australian and international photographers, and was coordinated by Dawne Fahey of the FIER Institute with Sandy Edwards contributing to the image selection. The assembled body of work presented insights into how photographers ‘read the landscape, both visually and psychologically through their images.’

..

The photographs, created in Australia, Asia, New Zealand, USA and Colombia are intended to inspire viewers to consider how ‘elements effecting the landscape unite us, regardless of our differences or the distances that occur between us.’ Through the photographs there is also an intention that the ‘poetic fragments presented by the work will connect with the viewer’s own memories, experience, or sense of place.’

The exhibiting photographers are: Ann Vardanega (Australia), April Ward (Australia), Beatriz Vargas (Colombia), Gavin Brown (Australia), Michael Knapstein (USA), Robyn Hills (Australia) and Pauline Neilson (New Zealand) and the exhibition and book are on show at Pine Street Gallery, 64 Pine Street, Chippendale, Sydney until May 31, 2014.

See more at: http://www.pinestreet.com.au and http://fier.photium.com/around-the-world-in-14 – sthash.QPto0nz4.dpuf

The exhibition and book launch took place on May 20, 2014 at the gallery.

My essay discusses issues that relate to the premise of the exhibition as well as some personal observations of the idea of the photographer in the landscape. The essay is presented here and at the end of the post I have included a selection of images and installation photographs of the exhibition.

.

.

All landscape photographs are history

It is vain to dream of a wildness

distant from ourselves. There is none such.

In the bog of our brains and bowels, the

primitive vigor of Nature is in us, that inspires

that dream.

Henry David Thoreau, journal, August 30, 1856 [i]

Around sunset, Northern Territory time, a gathering of photographers will assemble in the central Australian desert and witness the now iconic sunset at Uluru. What they encounter will be a lived experience and there can be no doubt that cameras, both with and without telephony capability, will record the moment. Their images will bear metadata of the shutter speed, aperture, camera brand and model, the time, date and perhaps even its geolocation. These images will be cast into the Internet as evidence for friends and family to see – a private experience shared and made transferrable by technology.

What then of the subject of their gaze and activity – the landscape? For this rock in the desert, the next day will be a repeat of this photo ritual, and each day after, it will be repeated again and again. Does Uluru wait for its activation at each sunset and each shutter’s click? This landscape has experienced a few hundred million years of sunsets and its current fame as a photo celebrity, is a mere blip in its history. Every day will be different and thousands of days, well, not much change. However, today’s photograph, even a split second after its capture, is history.

For a number of years I have cultured the belief which was informed by a statement attributed to photographer Minor White: ‘No matter how slow the film, Spirit always stands still long enough for the photographer it has chosen.’[ii] My variation is that that landscape reveals itself to the photographer of its choosing. Writer and critic John Berger adds to this discussion by proposing that there is a ‘modern illusion concerning painting … is that the artist is a creator. Rather he is a receiver. What seems like creation is the act of giving form to what he has received.’[iii] Could it be then that the landscape is the director and commissioner of the image that the painter or the photographer makes, and that the photographer – the right photographer – is merely the vehicle for the landscape’s transformation of itself into an image?

Like portraits that have been made since the beginning of photography, and the documents of human endeavour, commerce, existence and experience – time, or rather the passage of time, has granted then their relegation to past. Each photograph in this book is then a history image. The moment and space depicted wrenched from the continuum of time by whatever forces brought together the photographer and the landscape. A landscape image at that moment of capture is at once the subject photographed and also a time machine. Viewed on its own by its maker the photograph can be a comfortable aide memoir, and operate just as a photo of a loved one or a family wedding would do in its frame on the mantelpiece – the photo exists, and so too the remembrance of subject it represents.

But photographs are more than things; they are experiences. Photographer Ansel Adams attributed special values and meaning to his landscape photographs and sought to represent the landscape as being more than what it was physically. Simon Schama in his book Landscape and Memory cites Adams as commenting that: ‘Half Dome [in Yosemite National Park] is just a piece of rock … There is some deep personal distillation of spirit and concept which moulds these earthy facts into some transcendental emotional and spiritual experience.’[iv] Adams inspired the American nation and created a tradition of environmentalism and black and white photography that continues today.

For Australian wilderness photographers Adams’ ‘emotion and spiritual’ connection with the landscape is salient. In the book Photography in Australia Helen Ennis discusses how photographers of this genre engage with their landscape subjects. She quotes Tasmanian photographer Peter Dombrovskis entering a ‘state of grace’ on bushwalks when, ‘days away from “civilization”, he felt what he described as, “a sense of spiritual connection with all around – from widest landscape to the smallest detail”’.[v] Ennis also comments that wilderness photographers use a range of techniques to ‘lift the experiences of viewing the photographs into a realm that goes beyond the human exigencies of normal daily life.’[vi]

In a book such as this, as we turn the pages, what is presented to us is the photographer’s concept or story encoded in visual form. As with Berger this may constitute the next generation of ‘giving and receiving’. They may have made the photograph/s with a specific objective in mind – a narrative angle, the idea of showing something that stirred them that they wanted to share – or – from the earlier discussion, what the subject wanted revealed. But in the space between the giver (the photographer and this book), and the receiver (you, the viewer), another hybrid narrative emerges. The photograph acts as a stimulus on the viewer and an idiosyncratic response is generated. Roland Barthes uses the term ‘detonate’ to describe being in front of a photograph. In Camera Lucida he comments that: ‘The photograph itself is no way animated, … but it animates me: this is what creates every adventure.’[vii]

In photographs we are not so much connected or united with the landscape, but rather the experience of the landscape and the trees, rivers, blades of grass and rocks that are represented in images. In effect we are united by the landscape of photography and the gift that we can share through it. We can then, through photographs enter into a Barthesian adventure. Perhaps these landscape photographs are more than history – they are: an experience shared, an unexpected encounter, an adventure. In your turning the pages – then pausing to view each group of images, to contemplate and consider the communiqué stimulated by them, these photographs become part of your history, your experience, and your adventure as well …

Dr Doug Spowart April 17, 2014

[i] Schama, S. (1995). Landscape and Memory. London, HarperCollins, epigraph, n.p.

[ii] http://www.johnpaulcaponigro.com/blog/12041/22-quotes-by-photographer-minor-white/

[iii] Berger, J. (2002). The Shape of a Pocket. London, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, p.18.

[iv] Schama, S. (1995). Landscape and Memory. London, HarperCollins, p.9.

[v] Ennis, H. (2007). Exposures: Photography and Australia. London UK, Reaktion Books Ltd, p.68.

[vi] ibid.

[vii] Barthes, R. (1984). Camera Lucida. London, UK, Fontana Paperbacks, p.20.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

The photographers retain all copyright in their photographs. Some texts are derived from exhibition documents. Text and installation photographs © 2014 Doug Spowart and Victoria Cooper

.

.

.

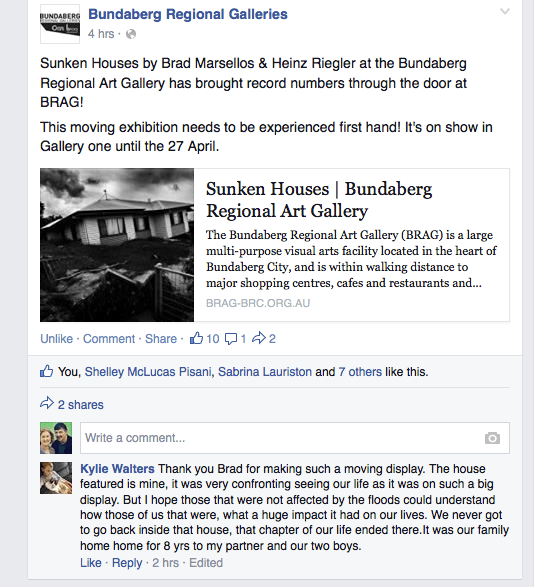

CAN ART BRING CLOSURE TO COMMUNITY TRAGEDY?

.

CAN ART BRING CLOSURE TO COMMUNITY TRAGEDY?

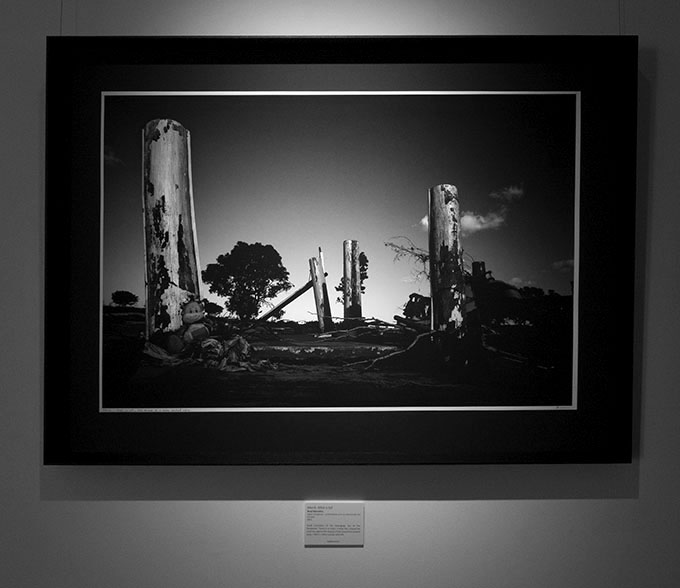

The exhibition SUNKEN HOUSES by Brad Marsellos and Heinz Riegler, Bundaberg Regional Art Gallery, March 12 – April 27, 2014

I’m standing in a dimly lit gallery surrounded by large-framed dark black and white photographic images. A somber soundtrack plays echoing the mood of the visual imagery. From outside the sound of rain pelting down enters the space and mingles with the exhibition’s audio. Rain is a sound that may normally not present a concern, particularly in a country frequently in drought, however the exhibition before me represents the effect that significant rain and runoff can have on our communities.

.

.

Just over twelve months ago, after days of torrential rain, the Burnett River at Bundaberg broke its banks submerging residential and commercial properties across the town. River cities historically deal with these events, however on this occasion the power of the river, and the duration of the flood, meant that after the water’s subsidence a significant area of urban space was obliterated. North Bundaberg suffered the most with houses washed off stumps, crashed into other homes and disappeared. What was left was utter devastation and a community dislocated, angry and in shock. The flood torrent had taken homes, belongings and also the sense of place and comfort that one feels in ‘being at home’.

Over those days the town had its heart wrenched from its foundations. Recovery, rebuild and move-on are the common expectations that usually follow such calamities. Government agencies and support groups rally in an attempt to facilitate the renewal and regeneration. However underlying the good works there still lingers memories, emotions and an all pervading the sense of loss.

When a community hurts the artist also shares that feeling and they may be called into service to make sense of, and perhaps through their art, help heal their community. So for local photographer Brad Marsellos, the story of the flood and the community became a 12-month project. Motivated to document and track the community’s response to the calamity Marsellos states he has: “… a strong passion for people and narrating lives, [and] believes photography allows the viewer to glance a moment in time and have the image take you on a journey.[i]”

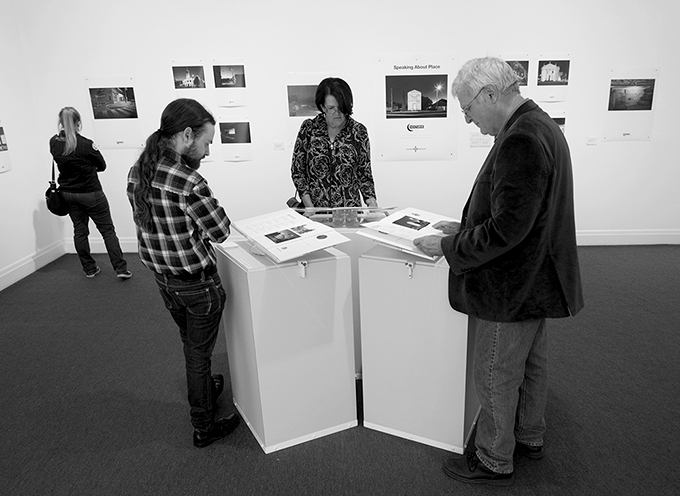

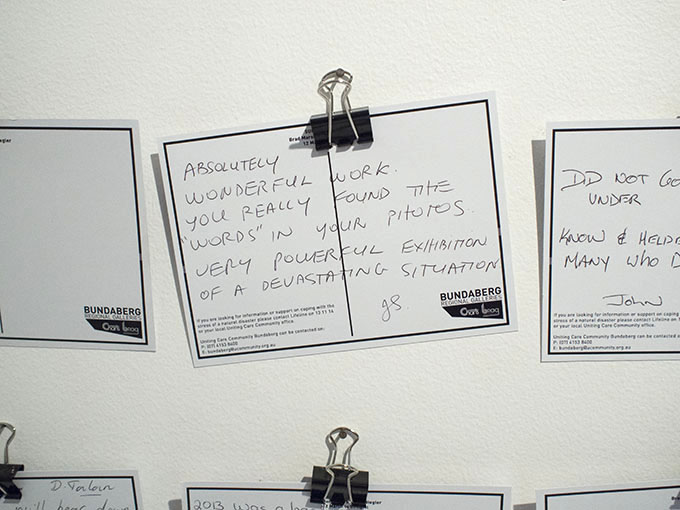

The exhibition Sunken Houses, at the Bundaberg Regional Art Gallery, is the public presentation of Marsellos’ commitment to his community and this documentary project. In the gallery large black and white photographs are presented in wide bordered black frames. The photographs capture a sense of impending doom through dark dramatic light, and often-stormy clouds.

.

.

The curatorship and gallery craft involved in this show intentionally creates a space for contemplation of, and connection with, images of a community still in the shadow of the flood. All lighting in the gallery is subdued with the images spot lit creating islands of light. The accompanying soundtrack is described by the artists as ‘an immersive and emotive score’, and pervades the senses of the viewer. The composer was Heinz Riegler, a multidisciplinary artist who lives and works between Europe and Australia. The musical score was designed by Riegler to not only compliment the photographs, but to also represent his personal response to the stories and emotions of the Bundaberg community.

.

.

Marsellos’ images go beyond the plethora of documentary and news images that were broadcast during the event and in its aftermath. These photographs, their presentation, and the musical score, work to touch directly with deeply etched memories of the flood. Writer and intellectual Susan Sontag in her book Considering the Pain of Others[ii], makes the observation that ‘pictures allow us to remember’. She adds that:

Harrowing photographs do not inevitably lose their power to shock. But they are not much help if the task is to understand. Narratives can make us understand. Photographs do something else: they haunt us.

.

.

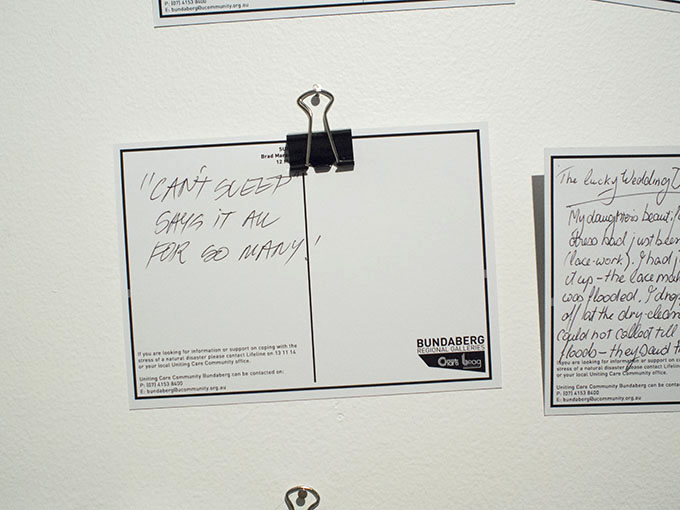

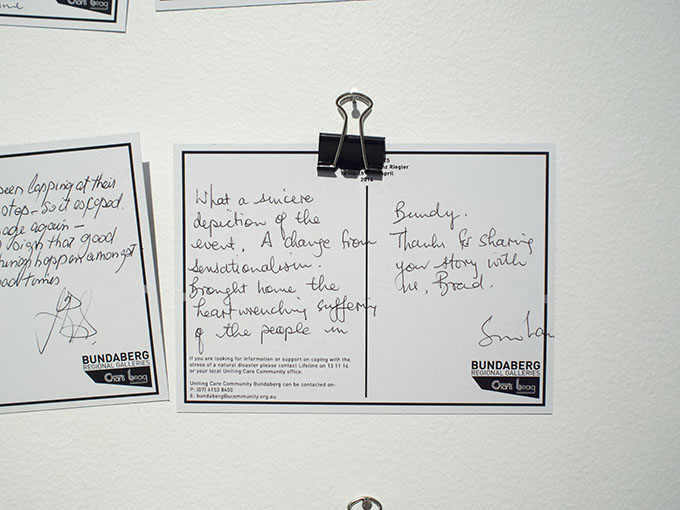

On their own these photographs may haunt and shock. Usually the viewer would leave the room taking with them the emotional state that was created in the gallery space. But this exhibition is different, there is a ‘message wall’ set aside in the gallery for visitors to tell their story – to express and share how they feel. Visitors either added to the wall or paused to read the cards and reflect upon the comments already posted. Perhaps this is evidence of the relevance that, ‘narratives can make us understand’, as Sontag suggests.

.

.

While the curation of the images, space and the musical score drench the gallery with a sense of tragedy and loss, the ‘message wall’ gives a release to the emotive tension. The combinative effect then of the exhibition is to create an overpoweringly emotional cathartic experience. First proposed by Aristotle, later by others including Freud, catharsis is considered as a psychotherapeutic treatment. Aristotle defined catharsis as: ‘purging of the spirit of morbid and base ideas or emotions by witnessing the playing out of such emotions or ideas on stage.’[iii] An exhibition like Sunken Houses may re-connect the community with memories and their experience of the event and through that connection provide much needed emotional healing.

Does the exhibition then function in a cathartic way? A Bundaberg News Mail report on April 16, 2014 published online, reported that the exhibition attendance had at that time broken all gallery records and stood at 2,500 visitors. In the article Brad Marsellos made a number of comments relating to the response of locals and out-of-towners to the exhibition and their reaction to the show.

“Every time I visit the space I read the many stories, messages of hope, recovery and continued struggles by members of our town that have been touched by this natural disaster.”[iv]

“Everyone has an experience of the floods and tornados – whether it be as an observer from afar, a flood affected resident or someone who is still rebuilding both physically and emotionally today and I’m honoured to think this exhibition is assisting some with their recovery process.”[v]

At a time when it seems that the importance of art and artists in the community is being downgraded by government defunding of art agencies, grants and opportunities for art education, it is humbling to see the effect that art can have on the community such as this. While the images may live on in the memories of those who witnessed the Bundaberg floods of 2013, the sensory experience of image and sound through the art of Marsellos and Riegler, will represent a compassionate and empathetic contribution – one that made a positive difference.

.

Doug Spowart

20 April 2014

[i] Gallery didactic panel

[ii] Sontag, S. (2003). Regarding the Pain of Others. New York, USA, Picador, p.89

[iii] McKeon, R., Ed. (2001). The basic works of Aristotle. New York, Modern Library, p.1458

[iv] NewsMail. (2014). “Sunken Houses exhibition draws a crowd.” Online. Retrieved April 16, 2014, 2014, from http://www.news-mail.com.au/news/sunken-houses-exhibition-draws-crowd/2231539/.

[v] Ibid

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

OTHER LINKS:

http://www.news-mail.com.au/news/sunken-houses-exhibition-draws-crowd/2231539/

Sunken Houses photographs © Brad Marsellos © soundtrack Heinz Reigler.

Installation photos and documentation of the artworks and review text ©Doug Spowart

.

My photographs and words are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/au/

.

.

.

.

.

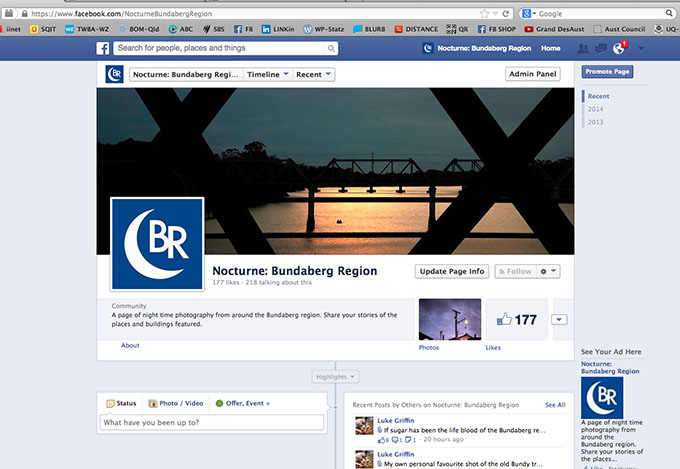

NOCTURNE BUNDABERG: A new community Facebook project

.

.

.

.

THE BUNDABERG COMMUNITY NOCTURNE

.

LINK TO FACEBOOK ‘Bundaberg Nocturne’

.

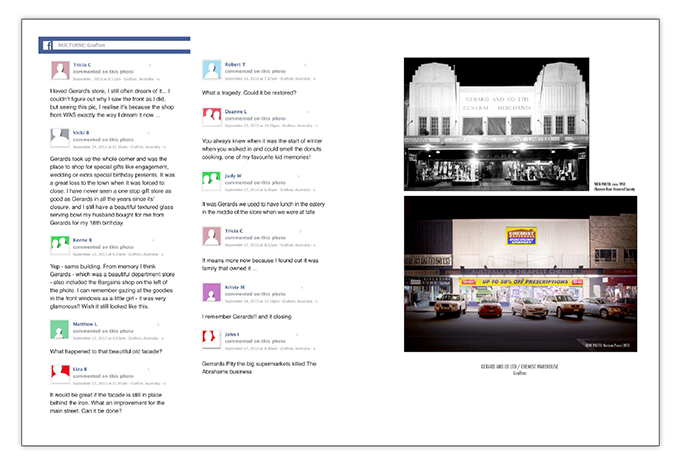

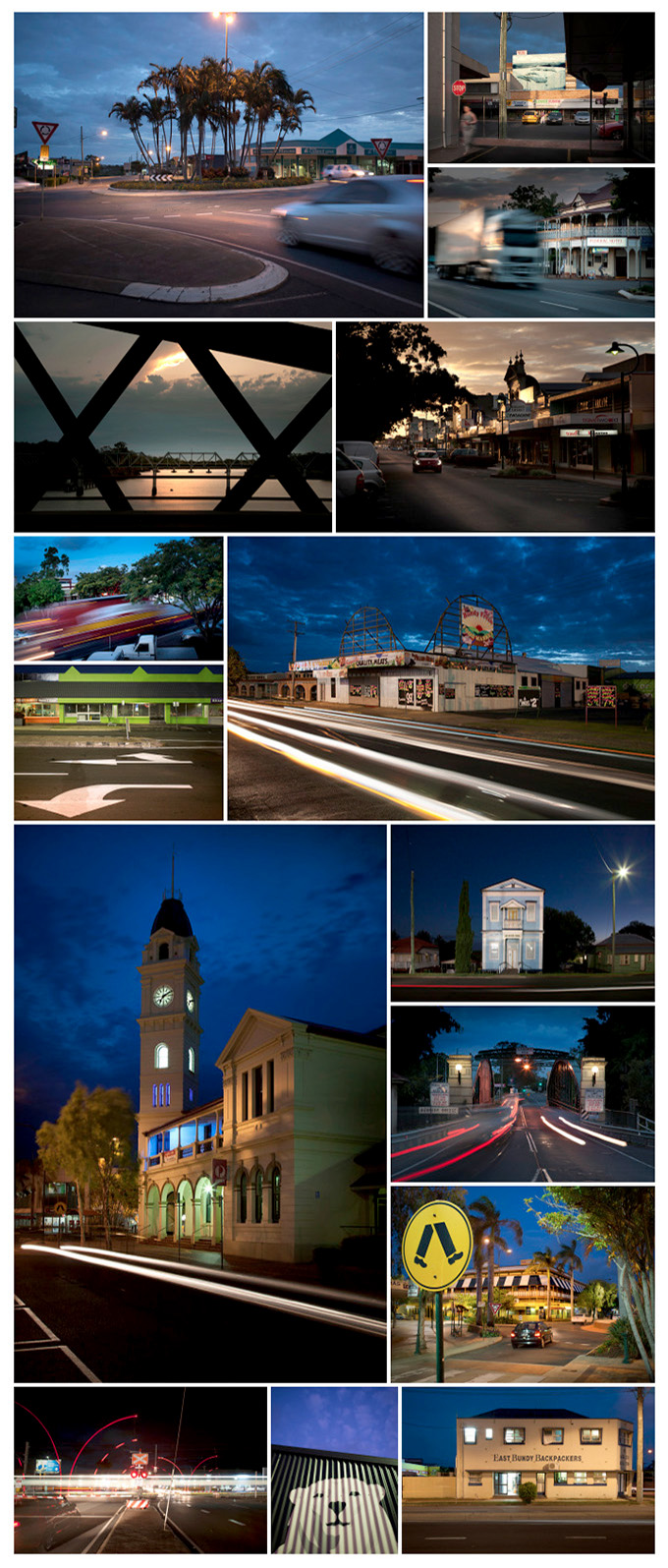

In our past Nocturne Artist in Residency projects in Grafton and Muswellbrook we were the photographers selecting and documenting place in the nocturnal light and then uploading the images of Facebook for community to see and comment. As part of the Queensland Festival of Photography 5 we were approached to undertake an Artist in Residency in the central Queensland’s Wide-Bay Burnett region. Centred on Bundaberg, Childers and local coastal towns, the project included an exhibition of our Nocturne works and a Facebook documentary project. On this occasion we decided to connect with local photographers to collaborate with us in the documentary project.

.

.

As a preliminary to the project we visited Bundaberg in early January and began initial documentary work. In the 1980s Doug had a significant connection with amateur photographers from the camera club movement in Bundaberg. For some time he had contact with the region’s photo guru Ray Peek so a visit to the hero of the Bundaberg’s photography scene was a necessity. So too was a connection with Shelley Pisani from Creative Regions and key people from the Bundaberg Regional Galleries including exhibitions Officer Trudie Leigo. The Facebook site was established, initial images were uploaded and ‘Page Likes’ attracted.

.

.

On our return in April we met with the group of Bundy photographers that applied to work with us through a formal Expressions of Interest process. A special Nocturne photography introductory workshop was conducted at which techniques and workflows were discussed and demonstrated. Of particular concern were issues to do with personal safety and security. Then the photographers were set loose to shoot subjects of personal interest, optimise them and upload to the Nocturne Bundaberg Region Facebook page. Within a few days the Facebook page had 180 ‘Likes’, numerous comments, shares and 3,500 views. Via an online group photographer participants were provided with support, feedback and mentoring to enhance their photoimaging skills. Although many are accomplished photographers, we were happy to work with those that required assistance or to review work when requested.

.

.

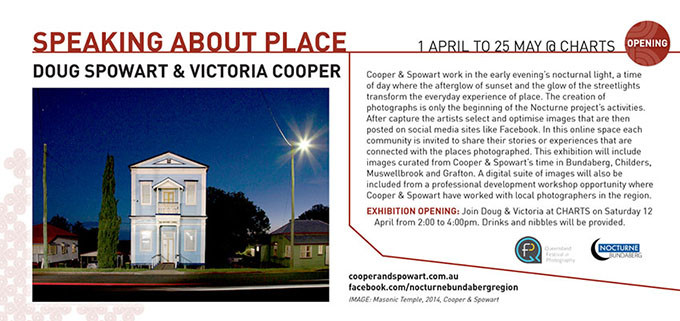

On Saturday the 12th of April our exhibition ‘Speaking About Place’ was opened at CHARTS gallery in Childers and the Bundaberg Regional community was fully engaged in the project. Over the next few weeks the addition of new photographs will continue and the community will be invited to begin a new dialogue about the region. They will, through the Nocturne Bundaberg Region project, be ‘Speaking About Place’.

.

.

The project will continue as a Facebook page and from this community resource may emerge exhibitions, books and other online opportunities. It is envisaged that many of the local photographers will make available images to the ‘Picture Bundaberg’ Archive, which is administered by the Bundaberg Regional Libraries.

.

The Nocturne Bundaberg Region Media Release follows:

.

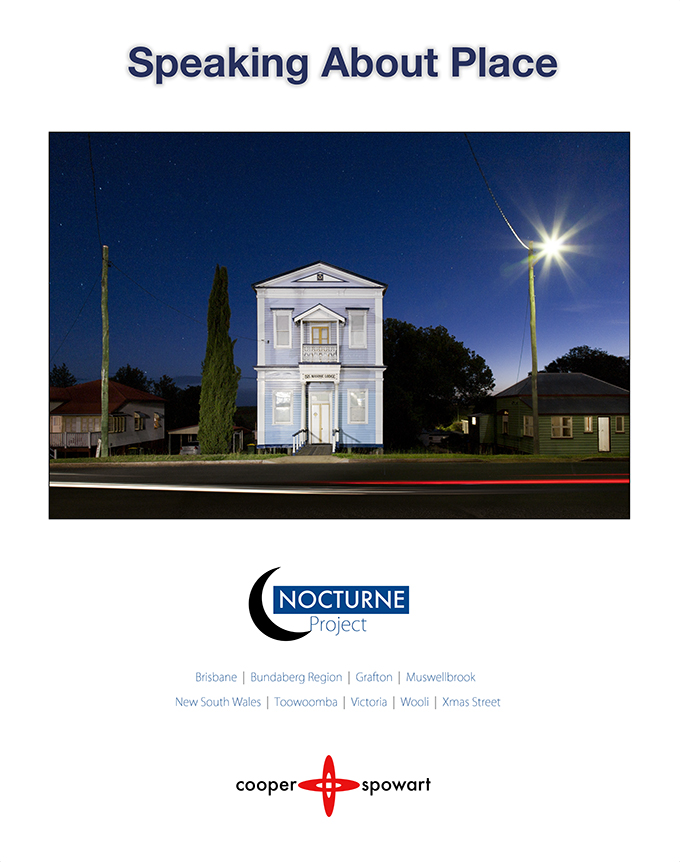

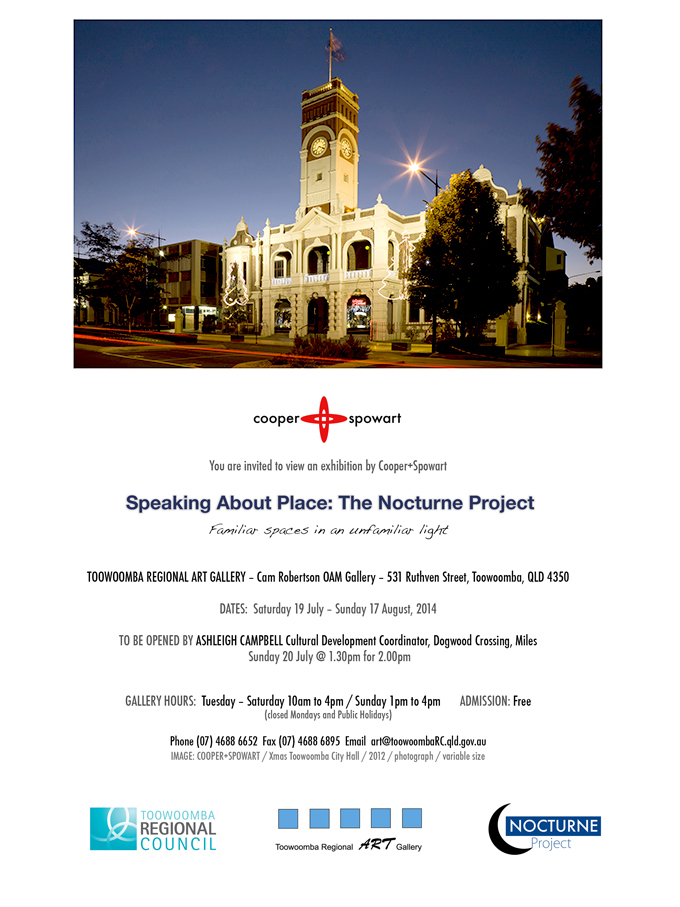

Speaking About Place: The Nocturne Project

Speaking About Place – an exhibition of collected images from The Nocturne Projects from Muswellbrook to Grafton as well as images from the Bundaberg region. Nocturne Projects showcase a variety of photographs highlighting the beauty of the early evening and its nocturnal light. Speaking About Place will be on show at the Childers Art Space (CHARTS) on Saturday 12 April in conjunction with the Queensland Festival of Photography 5.

Toowoomba-based photographers Doug Spowart and Victoria Cooper work in the early evening’s nocturnal light, a time of day where the afterglow of sunset and the glow of streetlights transform the everyday experience of place into something magical. Photographs created at this time require long camera exposures and therefore produce images that can capture blurred movement of people and vehicles.

“An important aspect of the Nocturne aesthetic is the affect of colour in different light conditions: ambient daylight, artificial lighting, car head and tail light trails. These images create a sense of drama, something that you’d generally see in a setting for a movie scene. It’s a place where stories could be told or evoked” Mr Spowart explained.

Spowart and Cooper initially visited Bundaberg early January to commence stage one of their Artist in Residence at the Bundaberg Regional Gallery. As part of the Speaking About Place exhibition, Nocturne Project: Bundaberg Region has selected 21 photographers from across the region to work alongside Spowart and Cooper through April. Photographers will have the opportunity to gain invaluable nocturnal photography skills from two leading artists. After the initial capture the artists select and optimize images that are then posted on social media sites like Facebook. Selected images will also be digitally displayed during the Speaking About Place exhibition.

“If a picture is worth a thousand words, how do you gather the thousand words from a community by showing them pictures of where they live? We aim to extend the experience and ultimately perception of place in the Bundaberg region. These are just some of the questions we’ll be exploring with the local photographers” Ms Cooper said.

Speaking About Place will be officially opened by the artists Doug Spowart and Victoria Cooper on Saturday 12 April at 2:00pm at Childers Art Space (CHARTS).

The exhibition will be on show from 1 April to 25 May and more information can be found via www.brag-brc.org.au, www.nocturnelink.com, and the Nocturne: Bundaberg Region project page on Facebook: www.facebook.com/NocturneBundabergRegion

.

A Queensland Festival of Photography 5 exhibition and project

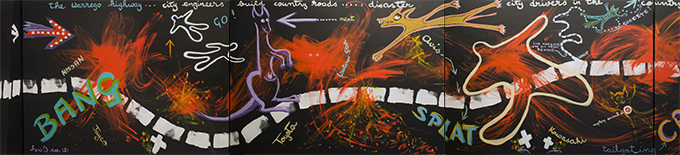

SWITCHING LANES: A new art show @ Uni of Southern Qld Gallery

.

Our camera obscura work and Centre for Regional Arts Practice Survey Books are included in this show.

USQ MEDIA RELEASE: Shining a light on the art behind the teachers

WE KNOW they must be good at their craft, right? After all, they are the ones responsible for teaching tertiary students in this region all about sculpture and painting and drawing and photography and graphic design and ceramics. They are the best in their fields. But all too often the artistic endeavours of our local educators is not seen by audiences because they are simply too busy to exhibit, or reluctant to sing their own praises, or far too focused on the raising the profile of their students’ work instead of their own. That’s where Simon Mee – Associate Lecturer (Collections Curator and Arts Management) at University of Southern Queensland steps in.He is curating an annual series of exhibitions featuring the artist behind the teacher.

Last year it was the work of local high school teachers that was showcased in an exhibition called “Not Just A Day Job”; this year the light will be shone on our tertiary educators in the “Switching Lanes” exhibition opening in the USQ Arts Gallery on April 1. “I don’t think we always get to see the art behind the educator,” Mr Mee said. “But an exhibition series like this allows teachers in the area to engage with each other and support the value of what we all do. “It’s also good to flip things over and show students what teachers can do and let the teachers lead by example.”

The “Switching Lanes” exhibition does not have a theme – artistic educators from USQ, the Bremer and Southern Queensland Institutes of TAFE were given carte blanche to create what they want. This approach guarantees enjoyment for audiences – there may be a few surprises amongst the artworks – but also provide the greatest learning opportunities for students.

“The upside for students is that they get to see artists push and play with their craft,” Mr Mee said. “It’s living practice, – it will have a raw edge – and if it’s a disaster, then students will learn from seeing that as well. Art is not about creating a product, but about taking risks and growing. It’s all about doing what you love.”

Switching Lanes will open at the USQ Arts Gallery on April 1, and run from 9am to 5pm, Monday to Friday, until April 23. Entry is free.

.

.

.

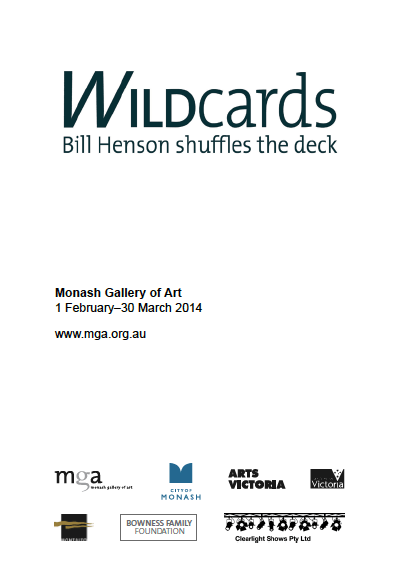

SPOWART: One of Bill Henson’s ‘WILDCARDS’

.

The exhibition WILDCARDS at the Monash Gallery of Art closed today. I was wanting to prepare a post that gave some backstory to my work that was selected by Henson to be in the show. I’ve been very busy, so I have not been able to prepare the full story. Later …

For the first time Bill Henson curated an exhibition of Australian photography.

Drawing on MGA’s collection, Henson selected around 100 photographs which have gripped, intrigued, or otherwise engaged him. This selection of photographs was arranged throughout MGA in an experience that will be as intriguing as it will be revealing of Henson’s sensibilities. The exhibition includes many rarely seen photographs, covering the history of Australian photography.

.

”All environments are immersive and so my intention, in so far as I am able, is to simply modulate the space, including changing the wall colour, the lighting and, of course, the placement of works so that enough ‘sympathetic’ space opens up for an unexpected intimacy to develop and, ideally, for the experience for others to be one which is powerfully apprehended but not necessarily fully understood.” Bill Henson about WILDCARDS.

.

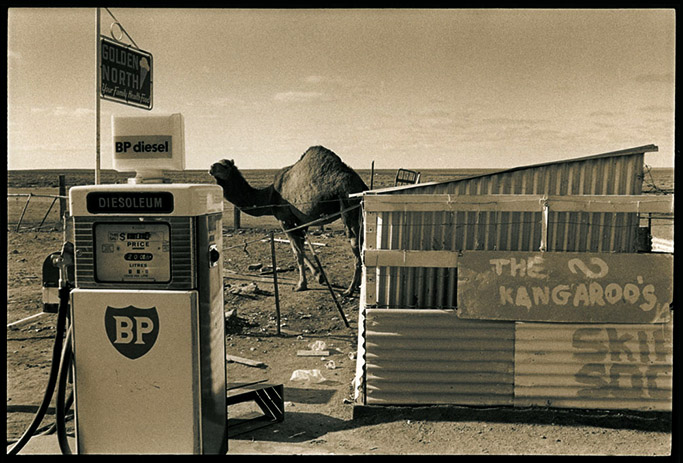

My photograph …

.

South of the border, Woomera 1983

sepia-toned gelatin silver print, printed 1986

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

acquired 1986

MGA 1986.44

.

.

Images: Courtesy of the Monash Gallery of ArtP. Photographs: Katie Tremschnig

.

.

.

.

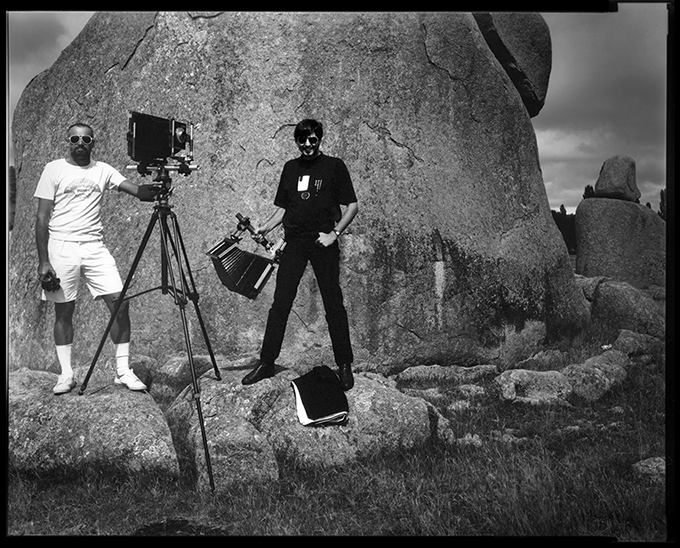

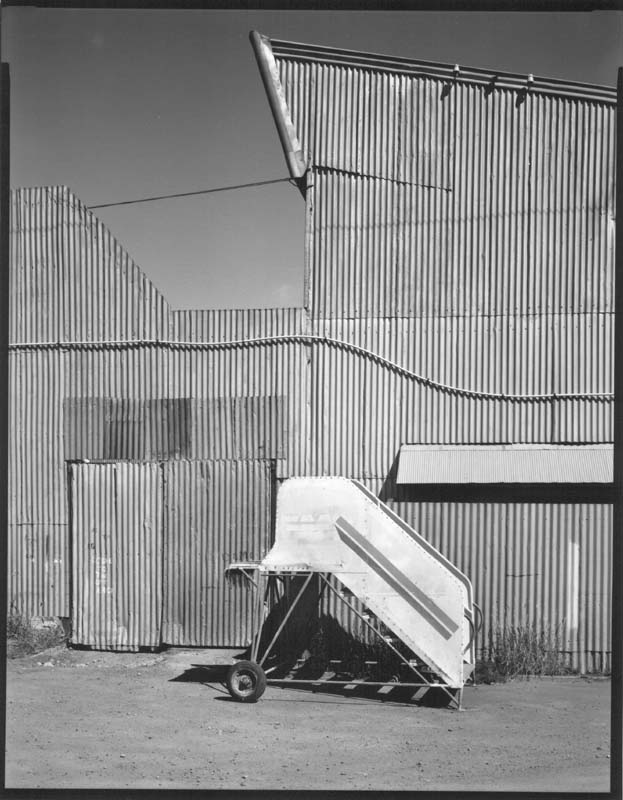

MARIS RUSIS: ORIGINAL PHOTOGRAPHS @ Gallery Frenzy, Brisbane

Masonic Hall, Barcaldine

.

The very nature of humanity is that each one who looks will see something different. So in these words, in this speech to open this exhibition, I’m in the privileged position to share what interests me about Maris Rusis’ original photographs. For a time I too was a disciple of the large format photography ‘zone’ – system discipline. I strove to develop what I’d call three skills: the conceptual – to see or previsualise; the technical to operate cameras and control chemistry; and the physical to lug the camera, all 50 kilos of it, to the place or subject of its use.

I found the romance of large format fieldwork is followed by the trial of the darkroom and the creation of a print reality – a manifestation of the subject as perceived by the photographer, at the time of capture. Chemistry, contact frames, darkness and the contemplative attention to time, temperature and agitation are an integral part of the process. So is, dare I say–image manipulation, dodging and burning-in to refine the distribution of tone, density and how these shape perception and direct the viewers eye as it rests on the image.

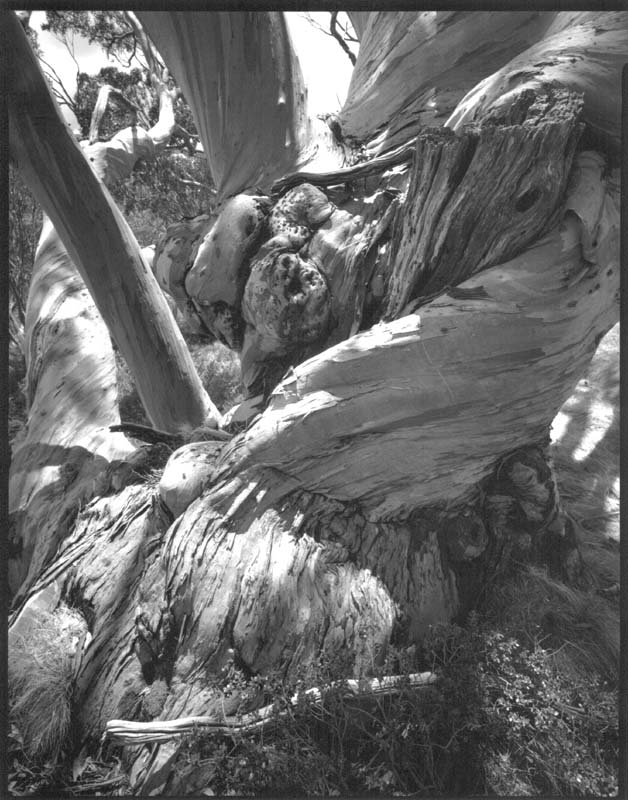

To bring an Australian light to the large format photograph Maris and I set out on a road trip from Brisbane to Canberra, Kosciuszko and Suggan Buggan in the late 1980’s. On this journey we shared rooms in cheap motels and backpackers, red wine and erudite conversation. Loading large format film holders in the cramped spaces of motel wardrobes and borrowed darkrooms we ventured into the high country and along roadsides. Photographing in the field was in part an endurance in the sweltering heat of mid-summer’s noon-day sun under the focussing cloth, and the privations of only being able to make 6-8 photographs a day – but each image was unique… a triumphant moment… a personal vision of light.

.

.

Part of our large format journey included special access to the vaults of the National Gallery of Australia’s photography collection. On opening, the light entered each solander box and we peered into the contents. We held prints by Weston – Brett included, Adams (Ansel–not Robert), Minor White, Emmet Gowan and others. These were the masters whose works we could generally only encounter on the pages of books usually at reduced size. I remember at the end of that day we stood on the exit parapet of the NGA, as it was in the old days, and you commented: “From today we can view the masters of large format photography with a new kind of arrogance”. Meaning that what we were achieving technically and conceptually matched anything we saw in the gallery’s collection. In reflection we did this in Australian light and of Australian subjects far removed from the well-trodden ground of the American tradition.

While I continued into the early 1990s hunting photographs with the SINAR 10×8 in the field, I was seduced to explore an expanding frontier of photography with Diana, pinholes and ultimately digital. Maris remained true to attitudes, values and approaches to photographic process and image quality that are the essence of the thing itself. Light-lens-silver – a direct and simple transference through photonics guided at every increment by the photographer and their vision for the subject before them. The plunge of the image-making world into digital technologies usurped and liberalised the terminology, in particular the words ‘photographer’ and ‘photograph’. Subsequently, it seems now with the emancipation of imaging anyone can be a photographer and anyone can photograph – it’s that easy.

There was a time when I, like many, thought a photograph was infinitely reproducible and that the darkroom was a machine for making multiples – but each was a little different. The speed and repeatability of digital imaging became the ‘machine’ where each print is identical. Now we can value each gelatine silver photographic print as a bespoke unique state object – a handcrafted image where as two can be identical. Maris once postulated a theory that the photographer, in printing their photographs – in particular with dodging and burning-in, created two images. The finished print is a secondary image of the subject before the camera – the first image being the negative, and as the photographer uses their hands to do shadowy light work they create a self-portrait primary image.

.

.

This evening, through the photographs that hang on these walls, an experience is shared. The title of the exhibition ‘Original Photographs’ may be exactly what they are. Our viewing position for this work as stated, is located in the digital age – where contemporary technology and process is arguably antithetical to the exulted practice that created these original photographic objects before us. Now I ask – should the provenance of these framed works make a difference to how we look at and think about these photographic prints? Should there be a precondition to viewing this work that requires a study of the technique, the myth, the challenges, incentives and the rewards of those who work this way, and how we as viewers should respond? Or should there be nothing of that. A photograph is before us – look, connect, interpret, respond … then, cast your view to the next.

What then of these photographs? Some may think that these prints may well be from a dinosaurian photographic tradition. For me their existence proves that the ritual continues and that the photographer’s vision and the seductive quality of the photographic prints that emerge from the photographer’s toil are still valuable contributions to the art. And therein lies the importance of Maris Rusis and his work. Few have walked his path in the sunshine of single-mindedness, about living one’s life totally absorbed, at whatever cost – family, friends, poverty and pleasure, all secondary to the pursuit of personal photographic nirvana, usually of the real large format kind. Edward Weston once stated: ‘My true program is summed up in one word: life. I expect to photograph anything suggested by that word which appeals to me.’ Maris Rusis and Weston have many things in common.

.

Doug Spowart

Written @ Girraween February 1, 2014.

.

.

.

Maris has written a reply to this post that adds to this commentary of his work:

.

It is an uncommon thing to invest some decades of effort in making pictures by one particular medium to the exclusion of all others. And an explanation is perhaps merited.

Firstly, everything Doug Spowart has covered in his blog is true and revalatory. It sets out key moments that propelled me in my committment to photography. And I thank Doug for the good start he gave me. But to keep going I had to support the conviction that my chosen medium has valuable properties that are not obtained or replicated by alternative means. I still continue to make pictures out of light-sensitive materials and offer by way of flagrant self justification the following essay:

In Defence of Light-Sensitive Materials.

The word photography was invented to describe what light-sensitive materials deliver: pictures that offer a different class of imaging from painting, drawing, or digital methods.

These “light-sensitive” pictures are photographs and the content of such pictures is the visible trace of a direct physical process. This is sharply different to painting, drawing, and digital imaging where picture content is the visible output of processed data. Some other imaging methods that do not process data include life casts, death masks, brass rubbings, wax impressions, coal peels, papier-maché moulds, and footprints.

There is a general idleness of thought that assumes any picture beginning with a camera is a photograph. Most casual references to digital pictures as photographs are motivated not by deceit but rather by the innocent and uncritical acceptance of the jargon “digital photography”; a saying which has become so banal and familiar that it largely passes unchallenged; except perhaps here, now, and by me.

I use light sensitive substances to make pictures because of the special relationship between such pictures and their subject matter. The wonder of this special relationship is also available to the aware viewer. Making realistic looking pictures long pre-dates photography. Old and new techniques include photo-realist painting, mezzotint, graphite drawing, gravure, and offset printing. Recently analogue and digital electronic techniques can deliver the appearance of abundant realism at trivial effort and cost . But although these pictures may mimic photographs but they do not invoke the unique one-step material bond between a subject and its photograph.

The physical and non-virtual genesis of pictures made from light-sensitive substances has far-reaching consequences:

Light sensitive materials are utterly powerless in depicting subject matter that does not exist. A true photograph of a thing is an absolute certificate for the existence of that thing; an existence proof at the level of physical evidence. Quite differently, data-based pictures at best approximate testimony under oath rather than evidence.

Light-made pictures require that the subject and the substances that will ultimately depict it have to be in each other’s presence at the same moment. True photographs cannot recreate times past. The future is similarly inaccessible. Since true photographs can only begin their existence in the fleeting present they constitute an absolute certificate that a particular moment in time actually existed.

Light-sensitive materials are blind to the imaginary, the topography of dreams, and the shape of hallucinatory visions. The option of making a picture from light sensitive materials offers an infallible way of distinguishing delusion from reality. A true photograph authenticates the proposition that the camera really did see something.

Light-sensitive substances neither selectively edit nor augment picture content. There is a one to one correspondence between points in a true photograph and places in real-world subject matter. This correspondence, also known as a transfer function, is immutable for all subject matter changes.

The sole energy input for a true photograph comes from an illuminated subject. The pre-existing internal chemical potential energy of the light-sensitive substances is sufficient to generate all the marks of which a photograph is composed. Other external energy inputs are not required. Remember, photography was invented in, described in, and works perfectly in a world without electricity.

Pictures made from light sensitive materials are different to paintings, drawings, and digital confections in that their authority to describe subject matter comes not from resemblance but from direct physical causation.

It is these unique qualities of true photography, its limitations and its profound certainties, that keep me committed to the medium as an integral and original form.

My light-generated pictures are produced one at a time, start to finish, and in full by my own hand. The work flow is mine. No part of it is down to assistants or back-room people toiling to flatter my skills so I will feel good about paying their fee. I will continue to make pictures out of light-sensitive substances even if it comes to the point where I have to synthesise those substances myself.

.

MORE IMAGES FROM THE SHOW:

.

.

All photographs © Maris Rusis. Photograph of the two photographers ©Maris Ruusis and Doug Spowart.

.

.